A Dedication to Dom Phillips

A year after his death, remembering a friend's important contribution to dance music, saving the Amazon, and his desire for fatherhood

When he was killed in the Brazilian rainforest on June 5, 2022, along with indigenous activist Bruno Pereira, my friend Dominic Mark Phillips was nearing the completion of his book, How to Save the Amazon. Long before that, he was the influential editor of Mixmag during one of dance music’s most important eras. In the days and weeks following his death last year, so many beautiful tributes were written by those who worked with Dom and loved him. This obituary in The Guardian and Mixmag’s eulogy by his friend Frank Broughton will give you a sense of the immense loss in Dom’s passing. The Guardian, especially, continues to cover the story in depth. And if you want to learn more, start with The Bruno and Dom Project.

As the renowned editor of the UK dance music magazine Mixmag in the 1990s, Dom Phillips played a pivotal role during the genre’s groundbreaking decade.

Our paths first crossed in the early 90s when we were both navigating our respective magazines, with Dom’s legendary publication at the epicenter of the European music scene while mine was just beginning to flourish in the US. The early- to mid-90s marked a transformative period for the cultural landscape that Mixmag fervently championed. As a devoted follower, I eagerly purchased imported copies, along with other influential magazines such as Jockey Slut, DJ, and The Face. I endeavored to capture a semblance of their distinctive attitude and refined style within the pages of URB. While the British electronic music scene may not have been significantly more advanced than its American counterparts in many respects, it felt light-years ahead in terms of industry, artistic depth, and overall presentation.

In 1994, I had a serendipitous encounter with Dom and his deputy editor, Andy Pemberton, in Manchester, England. Manchester, known as the iconic birthplace of early rave culture, was home to legendary acts like Happy Mondays, New Order, and the Hacienda (you can catch an excellent portrayal of this history in the film 24 Hour Party People). In those days, the city still had roving criminal gangs and fortified police vans stationed on street corners. Dom had already established himself as synonymous with the pinnacle of music journalism, so I was enthralled as I sat in a hotel room alongside him and Andy one evening. The two were recounting, matter-of-factly, their coining of the terms “Progressive House” and “Trip-Hop.” As somebody still honing his voice, I admired the editors’ uncanny ability to capture these nameless subgenres' essence effectively. In a time before the instant dissemination of slang and phrases via the Internet, it wasn’t easy to shape the cultural lexicon. And it took a particular competence to sift through the noise, give a fledgling trend a name, and plaster it across the newsstand for hundreds of thousands of readers to eat up.

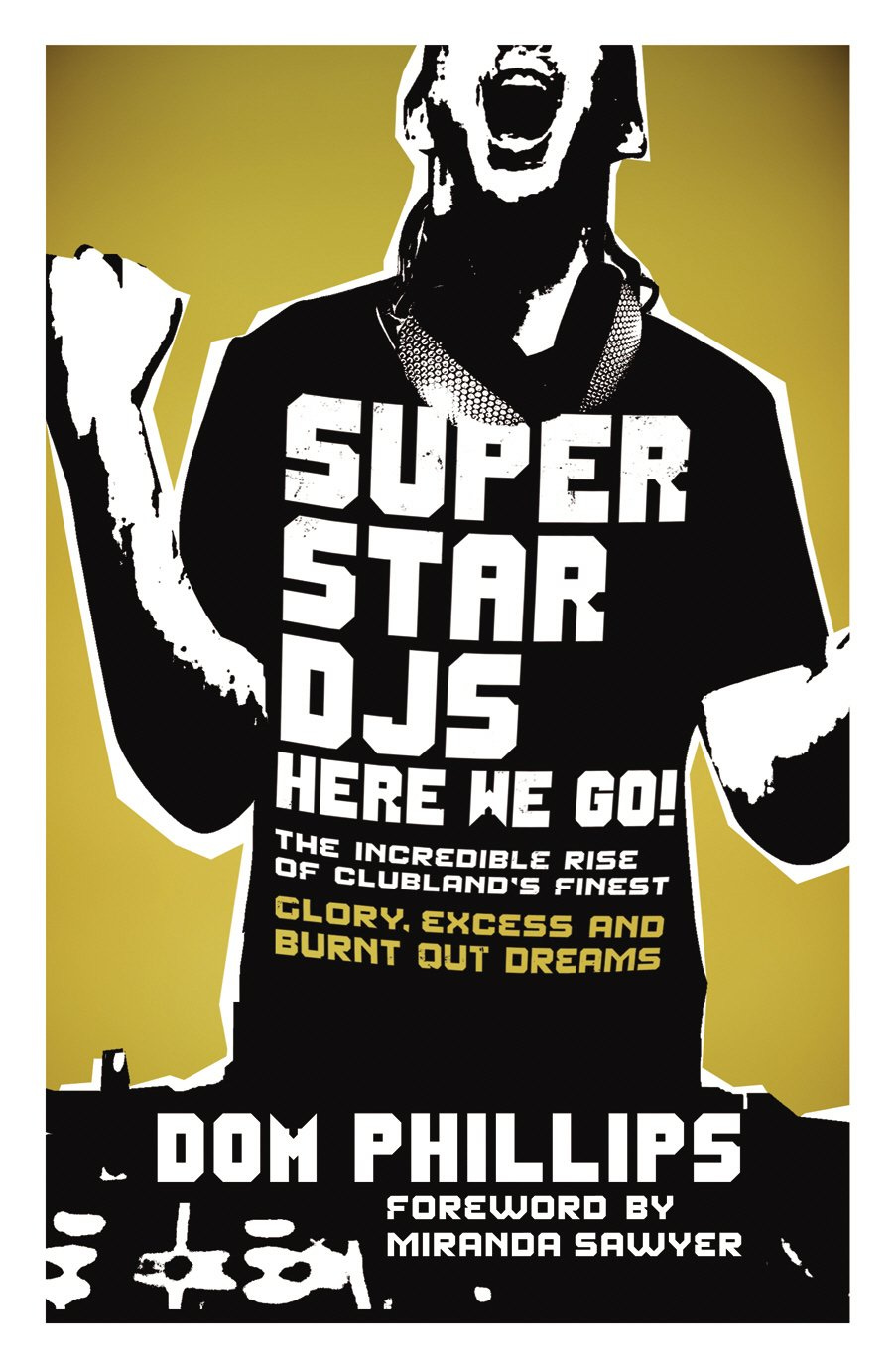

Despite the passage of time, Dom and I kept in touch periodically as our careers diverged, and those heady early days faded into memories. In February 2020, I was in Brazil co-directing a Coachella documentary during Carnival. Dom moved to the country in 2007 to complete his book Superstar DJs Here We Go and begin a new life. Given his deep understanding of local music and the political landscape, I arranged an on-camera interview with him at his home in Rio's Santa Teresa neighborhood. Unaware of exactly how tenuous his profession had become, I sought his insights on our documentary’s subject Pabllo Vittar, a prominent queer artist navigating a society where the country’s president openly expressed hostility towards the LGBTQ+ community.

When Dom requested that we refrain from filming in a way that could reveal his location, I realized the gravity of his work.

Dom's reputation as a prominent contributor to publications like The Guardian and The Washington Post, particularly for his coverage of local politics and the turbulent presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, made his journalistic endeavors increasingly perilous. In Brazil, being a journalist, particularly one who fearlessly sheds light on the country’s environmental and political challenges, is far from a safe profession. The documented abuses and dangers associated with such work were well-known to Dom, and he approached his role with caution and calculated risk. However, when he requested that we refrain from filming in a way that could reveal his location, I realized the gravity of his work. It was a pivotal moment that underscored the stark disparity between our respective playing fields. I would capture my video footage and return home to a country where I could freely disseminate its content without fear. In contrast, Dom would persist in pursuing and documenting stories that placed him at continued risk.

The last time I saw my friend was on Copacabana Beach, right after a tropical rain near the end of our week of filming. With my departure scheduled for the next day, we made plans to meet for a beer. We found a small beachside stand and sipped our drinks as we discussed life, work, and family. Dom even indulged me while I went for a solitary nighttime swim in the warm Atlantic Ocean. During that trip and subsequent WhatsApp chats, he kept me updated on his and his Brazil-born wife Alessandra’s quest to adopt a child, something they’d been working on for a while, but with no luck. Dom was desperate to be a father, but navigating local adoption complexities was difficult and would worsen as Covid enveloped the country. His longing for fatherhood deeply resonated with me, and I could see how much it meant to him.

Dom was desperate to be a father, but navigating local adoption complexities was difficult.

Dom was neither foolish nor cavalier, but his journalistic courage surpassed mine, leaving me concerned. My heart sank when I received a text informing me that he was missing early last June. In a desperate attempt for answers, I sent him a WhatsApp message, hoping he would respond by some miracle. “My brother, I wish I could speak to you right now. I wish there was something I could do,” I wrote. But I was too late. Dom was already gone, though it would be days before we knew what had happened.

Whenever somebody suddenly gets ripped away from us, beyond the sadness, there can be some level of guilt or regret. I wish I’d taken Dom up on his invite for a standup paddleboarding session off the Rio coast, a pastime he loved to share with friends. Or I could have surely made a better effort to stay in touch as I look at his unanswered chats near the end of his life. Or maybe even, as unrealistic as it is, I could have kept him safe or deterred him from venturing off on that last trip. None of this thinking can change what happened, so all I can do is celebrate his profound and lasting influence and do my best to support the continuation of the work he gave his life for.

Thank you for writing this. The thought that something like this could happen to one of our own still shocks me to the core. This is such a wonderful tribute to his life and work, and a reminder to reach out to those we care about. My first thought after reading this is who should I reach out to today. So, thank you.

You have made him come alive again.