Common: Conscious Rap, Album Misses, and Rooming with J Dilla (2005 Interview)

Career liner notes from the conscious rap icon

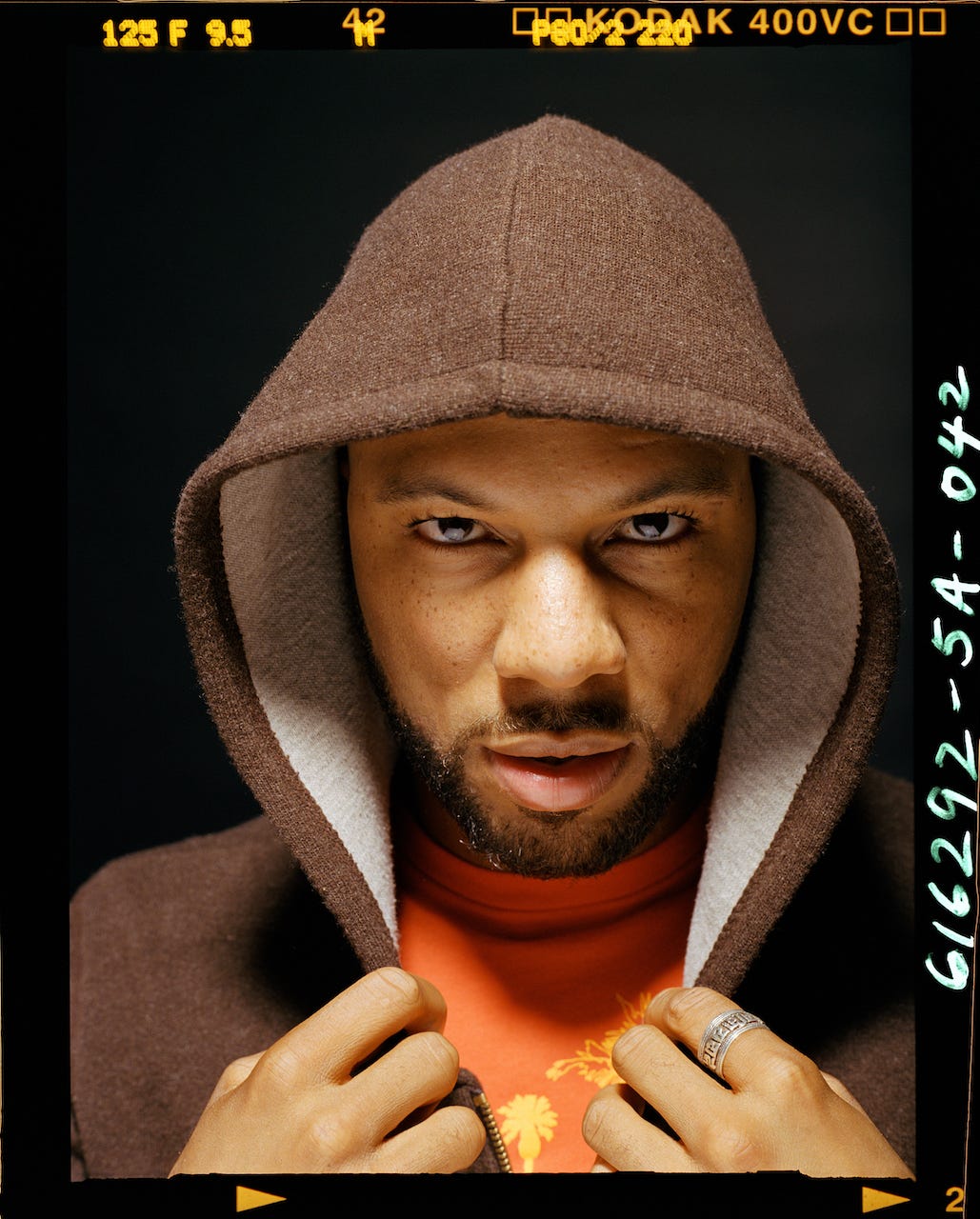

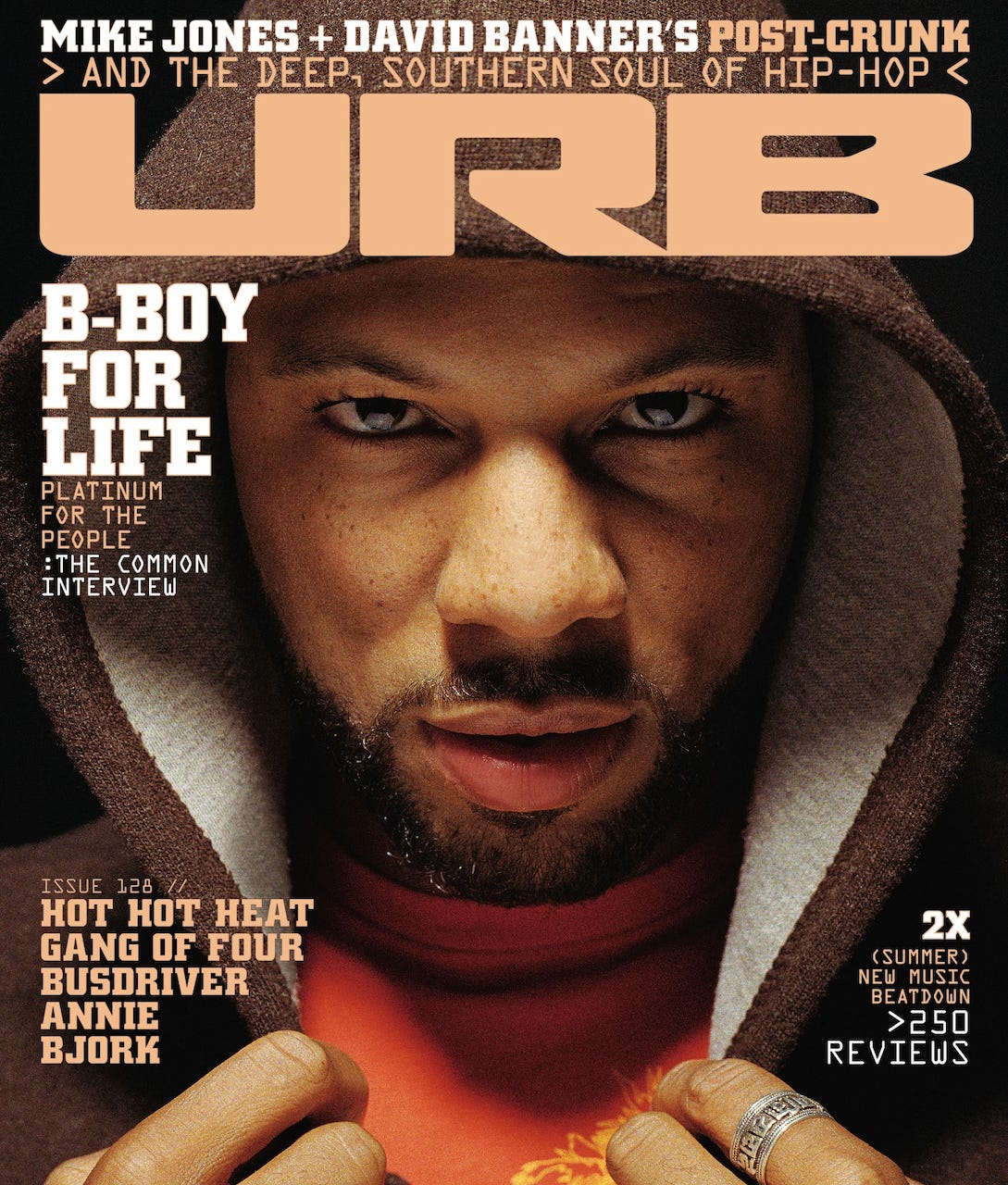

Our July/August 2005 Cover Story

B-Boy for Life

By Oliver Wang

Photography by Michael Schreiber

True story: I flew down to Los Angeles to interview Common, and when I boarded my Southwest flight, I sat next to someone who looked much like actor Taye Diggs. Then I realized it was Taye Diggs. My first thought was, “Taye Diggs flies Southwest? Like whoa.” The second thought was how serendipitous it was to sit next to the star of Brown Sugar, a movie that’s practically a cinematic interpretation of Common’s 1994 single, “I Used to Love H.E.R.”

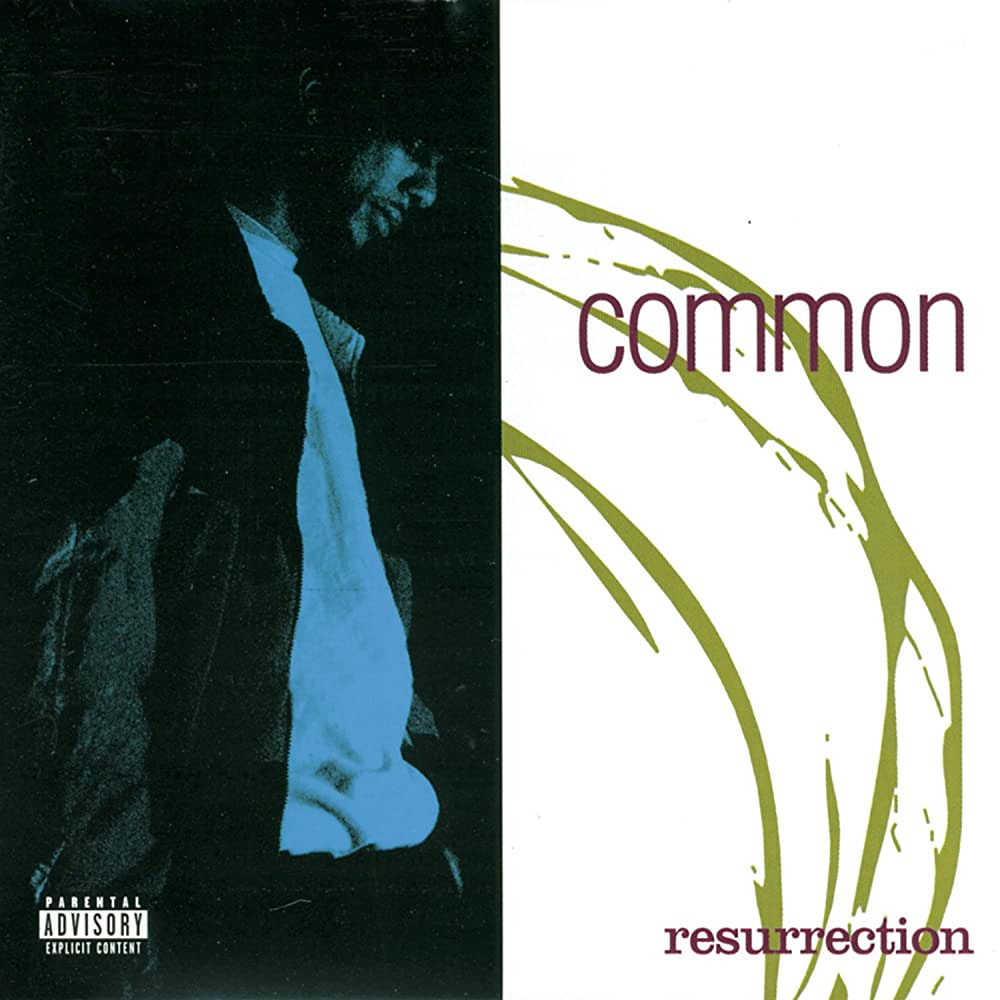

The enduring legacy of that song, even 11 years later, has been both a blessing and curse for Common. Though it and his 1994 Resurrection album helped propel the Chicago native into the inner sanctum of post-New School MCs, alongside A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, Nas, et al., it also created unrealistic expectations by fans who wanted him to take up the post as hip-hop’s moral authority and enforcer. Common had other ideas, though.

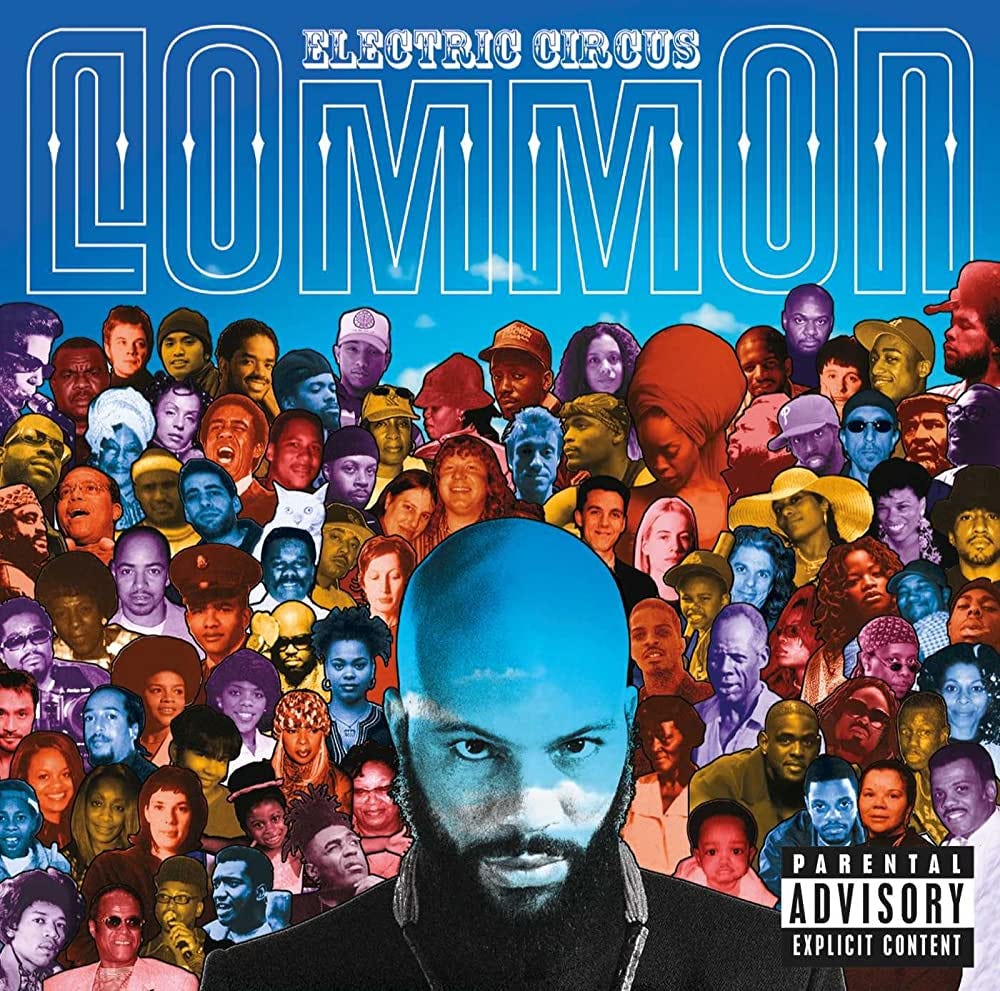

His next three albums — One Day It Will All Make Sense, Like Water For Chocolate, and Electric Circus — each revealed more layers to Common’s personality: his evolving spirituality, emotional struggles, narrative imagination, etc., all the while reminding folks that he was, at heart, just another “hungry hip-hop junkie in the city.”

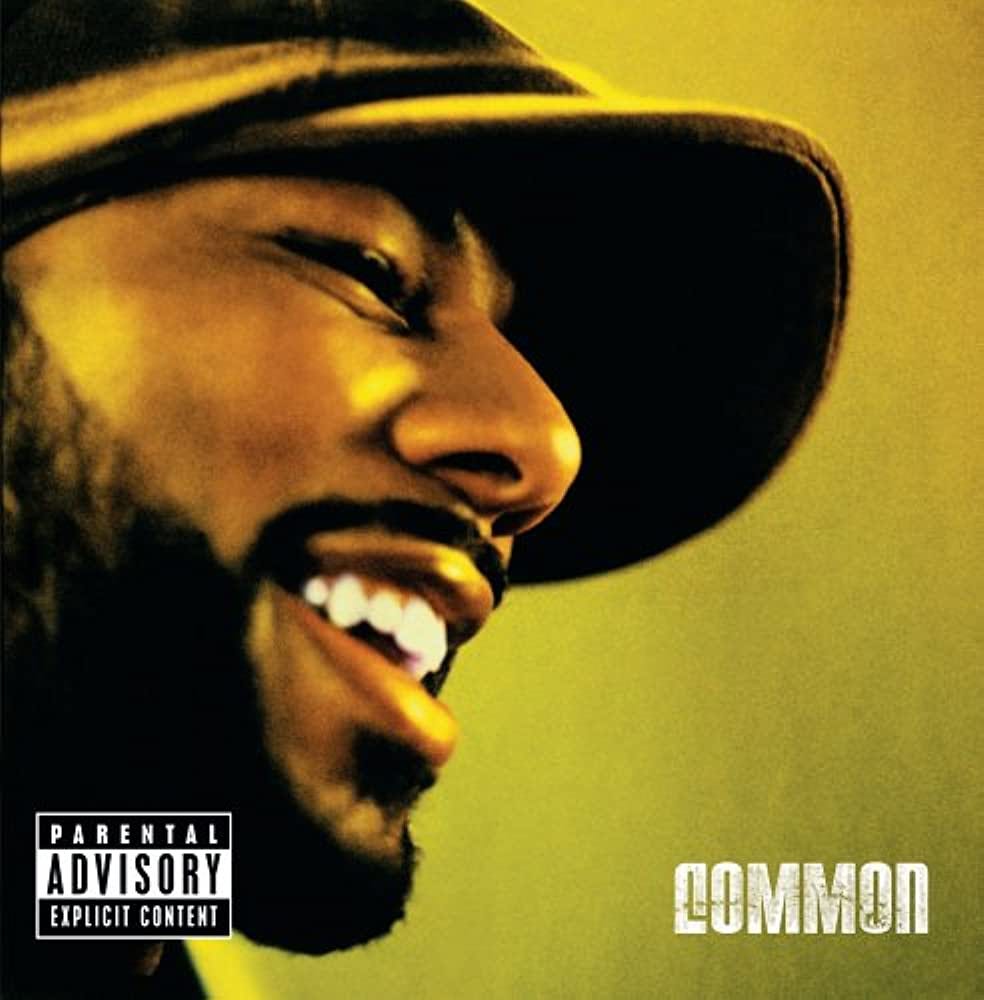

Fans grew with him throughout, but the ambitiously experimental (and vastly underrated) Electric Circus (2002) left more folks scratching their heads than nodding them. With Be, his sixth album, Common returns to the corners as a crossroads, finding his footing again and recording what’s already been heralded as one of the best albums of the year. (Just don’t call it another Resurrection — he’s been here for years).

Nowadays, Common splits his time between Chicago, New York, and now Los Angeles, where he shares an apartment with producer Jay Dee. URB met with Common in West LA to talk about his new album, raising kids on hip-hop, and whether he’s the last real conscious rapper alive that’s official.

“Kanye called me to come to the studio. I got there, and he was making this beat and looking at me like, ‘Man, you know this beat is dope right here.‘ He asked me did I want it… That became ’The Food.‘”

URB: You’ve been in LA for over a year now. What prompted you to get a place here?

Common: I was out here a lot and really loved it: the sun, the mountains, the water, the friends that I have. I loved how free it made me feel when I was creating. I would be working, but I still felt like I was on vacation. So I drift a little more; I get the energy of this place. I just let my imagination go when I’m out here.

Your housemate happens to be Jay Dee. I imagine that must be a rather interesting experience.

It’s like waking up to dreams. This dude’s beats, his music, when he’s just playing records, it’s just incredible. So spiritual and soulful. Waking up and getting to hear some of that music is like the food that I need for the day. I give him his space, but then at the same time, he’s my brother. It’s like an artist’s dream to have Jay Dee in the crib, making beats. I’d always have to fly to Detroit to make sure everything was straight. Can you imagine some days waking up and hearing him making beats?

You started working on this album while in LA, right?

I was riding around in LA just before I moved out here. Kanye called me to come to the studio. I got there, and he was making this beat and looking at me like, “Man, you know this beat is dope right here.” He asked me did I want it — I said, “Yeah,” That song became “The Food.”

At that early point, did you know that you’d be working so closely with Kanye for the album?

I didn’t know he would be an executive producer or producing nine out of the eleven tracks. We just knew that we wanted to create [together]. Not only did we start creating together, but then we talked about me being on his label. It’s really been a great growth period, a growing relationship, creatively. Everything came about right, like the timing of it, me hooking up with Kanye. I had to get Electric Circus out of my system; that was part of my evolution.

What do you mean by “getting Electric Circus out of your system?”

With Electric Circus, I knew that I wanted to take it out there.[I was] listening to Jimi, Pink Floyd. I wanted to take it out there . . . and I went there. I’m very grateful that I did Electric Circus because it’s part of my inspiration, part of my body of work and creativity. Sometimes when you learn new music, you’re going to experiment and try new things.

Electric Circus took hard knocks from the critics, and more importantly, a lot of your fans say it’s their least favorite of your albums. Do you think you were unfairly judged on that album?

I don’t think it was unfairly judged. People have their opinions, and they’re going to feel what they feel. I think it was a case of me coming through the door with a certain look and a certain feel. I think I took a big jump. And what’s funny is people say to me, “Why did Ahmir [aka the Roots’ Questlove] and them give you that music?” And I be like, “Look, they don’t give me nothing that I don’t already ask for.” Ahmir used to ask me, “You sure you want to go this far? You’re taking them all the way to the end.” But I guess I wanted to because I knew this was a new beginning. I had to get to this new beginning. That was the end of that chapter, and I don’t apologize. I won’t say it’s the perfect record, but I feel like it was some good work.

I also think the album went over the heads of kids who are still clamoring for you to make Resurrection: The Sequel.

What’s so funny is when I came out with Resurrection, I didn’t know people liked it. They [now] say, “Yo, we want another Resurrection.” Where was ya’ll when the record sales were going on? I’m not mad at ‘em. I just didn’t know people were into that album like that.

I think it’s interesting that both you and Nas share similar kinds of fans. They’re stuck on Illmatic and Resurrection, respectively, and are disappointed when you don’t “go back” to that sound or style.

It’s like those albums represent a certain point and time for those people. They want to grab that time and never let it go. I don’t feel like I’m going to do another Resurrection. I can’t go back in time. How can you do that? I think [hip-hop] would get redundant. Because it changes every so often and evolves so much, it keeps fresh.

On the other hand, you had something to prove with Resurrection, and you’re back in that situation again with Be.

With Can I Borrow A Dollar? people didn’t really know who the hell I was. I wasn’t dead but didn’t nobody know me, so I came to life with Resurrection. I think the hunger [with Be] came about from the lack of response to Electric Circus and just people looking like “Aww, [ex-girlfriend] Erykah [Badu] changed dude.” That was the first time I had gotten ridiculed in magazines, so it was a challenge for me.

Something must have worked – more than a few publications have already anointed Be an instant classic. I know this is a loaded question, but do you truly think Be achieves that?

I felt it once we finished all the songs. I felt that it was going to be a classic. Everyone around us did too, and we don’t just have all head-nodding friends. A lot of my homies would let me know, “Yo, that’s wack. Why you got this going on?” They give you all their true feelings. I felt more than anything, this is some of my best work ever. My favorite album of mine is Like Water For Chocolate, and now it’s between Like Water... and Be.

One thing that jumps out at you about Be is how compact it is: 11 songs, less than 45 minutes. The last album I remember that short was Illmatic.

I felt in those eleven songs, I could say what I needed to say. I wanted to keep the best of the best songs; I didn’t want to put out anything that I was iffy about. I was doing everything that felt right. Eleven songs felt right. Honestly, I definitely felt like Illmatic was something I looked at. Illmatic, D’angelo’s Brown Sugar, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On? — classic albums that didn’t have so many songs.

You also only worked with two producers – Kanye does all but two songs, Jay Dee does the rest. That’s very unusual in an age where rap albums all seem like they’re produced by an ensemble.

Even If you look at Electric Circus, it’s basically focused on the Soulquarians, which is Questlove, James Poysner, and Jay Dee. They were producing as one unit. I ended up having the Neptunes do something on it too. Then with Like Water for Chocolate, it was the same thing: Jay Dee, Questlove, and Primo. That was my goal. This time, it turned out so fabulous too. I got two of the best dudes you could ever have. These dudes will go down in history.

I’m sure people will ask: you room with Jay Dee, yet he only did two of the tracks?

Jay Dee was going through a sickness, so he couldn’t produce at the rate that he usually did. I wanted Jay Dee for more. I worked out to some Jay Dee tracks, but whatever songs stuck with me [regardless of who produced them], I used.

It’s interesting to me that your two main collaborators on Be, as well as yourself, are all from the Midwest.

Definitely. We share a similar mentality. There’s a certain soul that you’re born with, coming from that place. Growing up in these blue-collar cities where there’s a rich history of jazz and blues and soul music. [Also], we don’t have the entertainment industries there. We don’t have cars come to pick us up in Chicago. We don’t see KRS-One walking down the street or Denzel Washington.

There’s something about being between spaces that resonates in your work. You have this line on Black Star’s “Respiration”: “My circumstance is between Cabrini and Love Jones” — even in Chicago, you see yourself in the middle.

I really found myself, so many times, in between those walks of life ’cause I grew up in a black middle-class part of Chicago. I grew up where my homies were gangbanging. Some of their parents were on dope, and some of them lost their parents to dope . . . struggles that I hadn’t even been through, but I was connected with them because they were my friends. I also got to be around private school honor students that went to the Jack and Jill parties, which is an upper-middle-class organization that is very bourgeoisie. So seeing all that, I got a sincere connection to both of those walks of life. I can be in between that and exist and be comfortable because I know each person’s struggle. That’s what I’m talking about with [Be’s] “It’s Your World.”

It’s now more than 10 years since you recorded “I Used To Love H.E.R.” What’s your relationship to hip-hop these days?

I don’t listen to it with the enjoyment the way I did [when I was younger]. It was so new, and I didn’t know about the business, it was just the dream of seeing people like me enjoying and expressing themselves. I do love certain things about it more. From a musical standpoint, I love the fact that we expanded it. I just love the fact that it has grown. Just from another perspective, I love that we can travel the world and the influence it has on the world. From a business person’s perspective, I love how it employs a lot of people from the community. From a creative perspective, I do like some of the quotes, but I definitely listened to it with more enjoyment [in the past]. Some of the only albums that made me feel the way I enjoyed it in the early days was College Dropout and The Black Album. I also love the song “Why?” by Jadakiss because of the words of the song. I was grateful [to be on the remix].

Speaking of The Black Album, what did you think when Jay-Z gave you that shout-out on “Moment of Clarity.”

I was honored. That was the ultimate shout-out, the ultimate love. He dropped a gem for me like, “Here this is for you, you better take it and go with it.”

But what do you think about the point he was making: that he couldn’t sell as many records if he rhymed like you?

Maybe that was true at that time. Maybe that time is changing. I don’t want to act like just because you talk about conscious things, it’s the reason you’re not selling. Sometimes music has to be extra good and universal. I think Kanye was a perfect example of that because in “All Falls Down,” he says some stuff on there. He says some conscious things on there.

“I’m proud to be called [conscious]. You’re looking at Bob Marley, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, KRS-ONE... When you look back in history, it’s going to mean something.”

These days, it seems like most rappers treat the label “conscious” like a kiss of death. They want to distance themselves from it.

When they started saying that to me, I was defensive the first time, like, “Why do they have to label me that?” Then I started looking more throughout music history at the artists they call conscious, and I’m proud to be called that. You’re looking at Bob Marley, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, KRS-ONE, that lineage right there? Okay, call me conscious. When you look back in history, if I’m labeled as a conscious rapper, it’s going to mean something. More than the booty-shake rappers.

It’s not like you don’t want to sell albums, though.

I would like to sell multi-platinum, but the majority of the reason is for survival and to be able to live. I also know that I can live doing other things, but I would like to secure some finances in this industry. I also want to say that I want millions of people to hear my music. I create this music so that the world can hear it. I gotta say — I want to create music forever. I don’t want to have to create music to make a living, but I want to create music.

You are branching out into other things, though, right? You have a new hat company called Soji. You’re acting. I saw you’re writing children’s books, too.

I’ve written three and started a fourth one. It deals a lot with self-esteem, self-love, and taking care of yourself from a child’s perspective. I was approached first by Scholastic because they did this thing called Hip-Kid-Hop. They had me, LL [Cool J], and Posdnuos from De La Soul all writing. I ended up writing one, but they never released it, so I ended up writing different ones. That’s how it began. I realized that not only would it be fun, it was going to be another way for me to really reach the kids in an authentic way. I’m not trying to sit up there and be the kids’ clown or nothing. Talking to them for real, the way I would talk.

I assume the fact that you have a seven-year-old daughter yourself factors in, too. I’m curious — does she listen to hip-hop? And are you concerned about what she listens to?

I care, but I just try to remind her of who she is and listen to her about what she wants to do. Talk to her about loving herself and that everything she hears ain’t literal. [I try] to explain, as much as possible, “Look, all this music is bullshit. You can dance to it if you want but don’t take it to heed. But, I ain’t going to tell you not to like it.”

Do you think she understands that?

Yeah, I think she does. She still sings the songs, but I don’t think she understands every lyric she sings. I told her about [Lil Jon’s] “Get Low.” I was like, “Okay, you singing this, but you know what this is, right? I just want you to know.” So she thought about it before she started singing it again. I’ve got to also remember: I was singing Rakim hooks, but I didn’t know everything he was talking about. I eventually learned and grew to understand more stuff. I want my lyrics to be like that - when a child can grow up and be like, “damn, he was saying that?”