Earthquakes, sub-bass, and aftershocks

A very personal memory of disaster and a dancefloor in '94

Memories can fracture and shift over time. But some can be vividly retold in technicolor clarity, even years later. The quote, “Journalism is the first rough draft of history,” declares the importance of documenting events and stories in the present. These accounts may not have the depth and analysis that comes with historical research, but they capture nuance, emotion, and real-time insight before those become diluted or lost over time.

This week is the 30th anniversary of the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the largest in LA history. There are, of course, the requisite historical reflections and images to jar our collective memory. But ask people who lived through it, and you’ll get personal stories from the mundane to the terrifying.

This is mine.

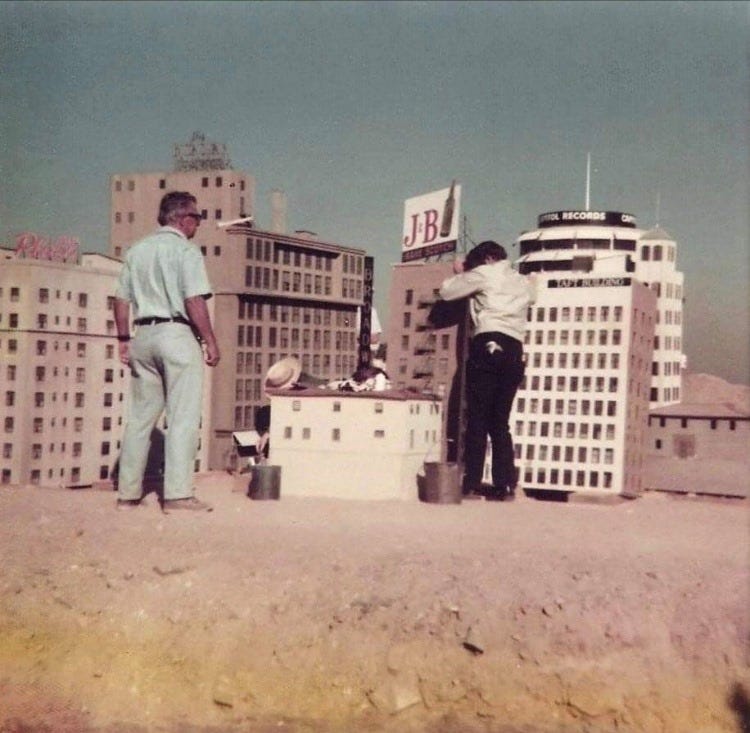

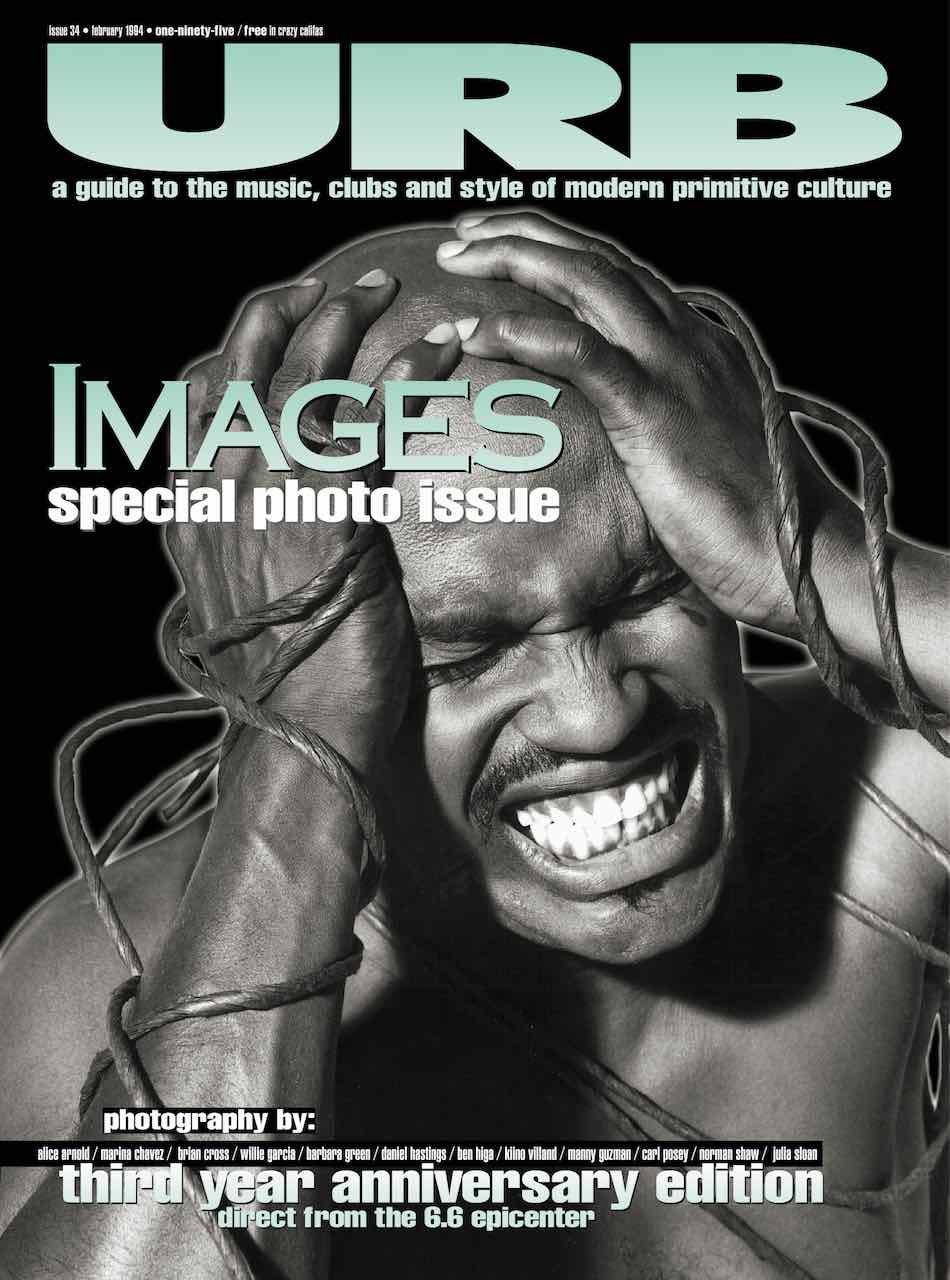

The once-famous Hollywood Taft Building stands like faded royalty at the legendary corner of Hollywood and Vine. Besides being LA’s first high-rise office building, it hosted last-century movie stars, high-powered publicists, and even a scrappy music magazine. In 1992, we moved URB from my live/work warehouse in the Crenshaw neighborhood to the brick and marble tenth floor of its new address at 1680 North Vine. Our masthead would now say, “High Risin’ Suckas,” and it was the first office I didn’t also call home.

In the ’90s, the world-famous intersection was more seedy than glamorous and had enough rough edges for our salad days. If I were working Saturday nights, I’d sit on the windowsill and look down to see a flock of sparkling lowriders slowly prowling the rowdy boulevard.

Thirty years ago, the ground below the nearby San Fernando Valley shifted violently at 4:31 am. A 6.7 magnitude quake jolted millions of Angelenos from their sleep. I hadn’t been to bed yet and was at work alone on the 34th issue of the magazine. I was suddenly in what felt like the worst place in an earthquake—trapped in an aging skyscraper.

“Well, it’s 10:22 in the evening, high up on the 10th floor of the historic Hollywood Taft Building, and even as we finalize the last few boards for printing, the Earth still trembles. Haunting aftershocks resound from the street level up through my feet, yet this time the sensation is of mild interest—a concern oddly subdued. At 4:31 a.m., yesterday morning, shit was a different story.”

Editor’s letter, Issue 34, February 1994

I can only count a few times when I thought I might die, but this was one of them. The building shook so hard that I couldn’t imagine how physics wouldn’t tear it apart. A bookcase fell, blocking an exit door. I moved through the dark to another doorway and ran down ten flights of stairs in my socks, sliding around corners like Tom Cruise. I don’t remember seeing another soul in the building.

My black Ford Explorer was parked in a lot next door. Part of the wall from the dilapidated Brown Derby, a golden age of tinsel town meeting spot, had fallen inches from my truck. I drove onto the same empty streets that had been full of youthful vigor 24 hours before.

The first stop was my mom’s apartment, just down the street from my office. Checking on my grandmother would take me through the quake’s epicenter. A dissolved hillside partially covered an abandoned car on the freeway. Not far away, a police officer had died after careening off a fallen overpass. Fires fueled by broken gas mains set streets ablaze as I drove through the Valley. Buildings sat at odd angles.

The transformed city was waking up in a daze. A salesperson the magazine worked with told me he was moving out of LA the next day. He couldn’t live in a place that was so unpredictable. My production manager retrieved his computer from our office hours after the shaking stopped, thinking it safer to work in a first-floor apartment. Experience a large earthquake or any of nature’s most formidable upheavals, and you understand how powerless that force can render you.

When I returned to the Taft later in the day, I answered a call from somebody in New York. It was the early nineties, so news traveled slower, and the caller wasn’t aware of the situation. I took the message, but only after mentioning the state of emergency.

Eerily, the “Taft Building” was destroyed in 1974’s blockbuster Earthquake. In real life, the building survived with a few cracks and still towers above the district’s resilient nightlife. During the quake, I felt completely alone. But as I drove around the city in the following hours, it was clear how communal the experience was.

The house that Junior built

Like global tectonic shifts, much of dance music lore also lives in our collective memory. Several months after Northridge shook, on the opposite side of the country, another late-night event left an indelible mark on my psyche. This time, thankfully, it was more life-affirming than threatening. 1994 was particularly memorable for one special club and its DJ.

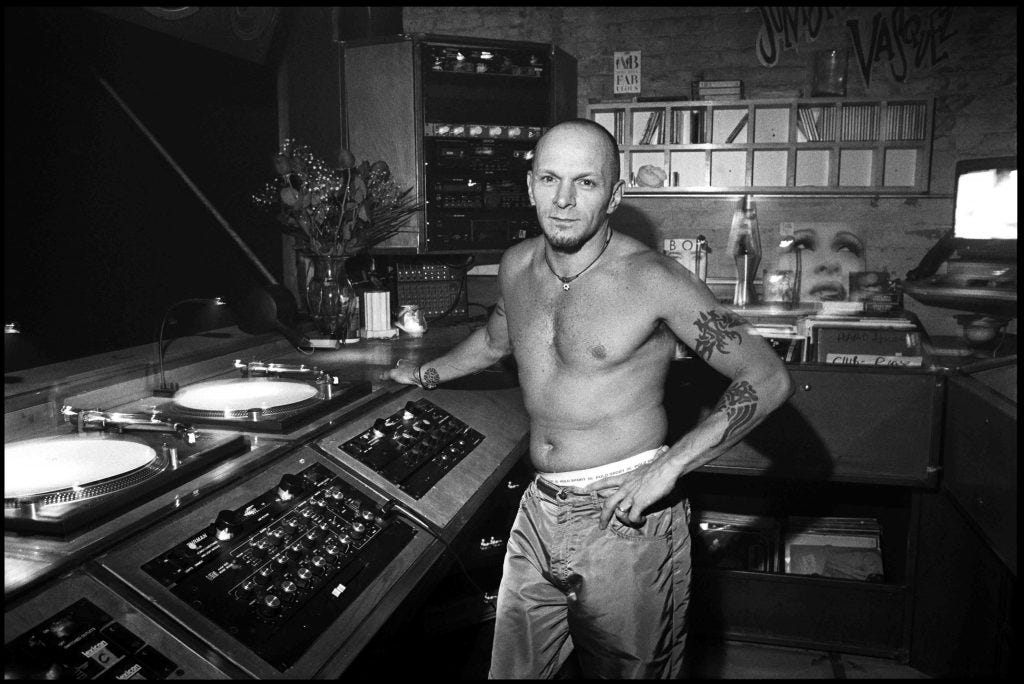

When I stumbled into it that July, during the New Music Seminar, Junior Vasquez’s Saturday night/Sunday morning bacchanal Sound Factory was already an institution. But that would be the summer it turned pretty. It felt like everybody was in the room on the night of NMS. I remember a young Mo’ Wax label founder, James Lavelle, being transfixed at the spectacle. By sunrise, everybody understood what they’d witnessed.

Sound Factory was alcohol-free, but other enhancements were easy to come by. Its Black and brown crowd was part of the vogue and ballroom scenes, which meant it was predominately gay. The shirtless, strutting, and confident boys were a little intimidating to a younger me. These weren’t the media-darling club kids of NYC’s Limelight, who were known for costumes rather than dancing.

Vasquez’s mixing style of long, trippy, blending transitions teased and morphed over minutes. The disorienting and hypnotic rumble came from a custom-built Phazon sound system designed by Steve Dash and Phil Smith. His DJ booth was the size of a small Manhattan apartment, high above the dancefloor. Sets might incorporate gospel and classic deep house vocals, even Gregorian chants. But they were also brutally heavy, with a pounding rhythmic percussion that bordered on techno. Vasquez ensured every aspect of the experience—lights, effects, sonic easter eggs—were designed to keep you lost in the music.

Djhistory.com’s Sound Factory history describes the room perfectly:

“It’s nine in the morning, sometime in 1991, and Junior’s been pumping the dancefloor since midnight. Glistening bodies are moving in shadow, a sea of dancers working with the steady power of a machine. Everyone is loose with angles and movement and focused on this single never-ending moment. The groove is repetitive, relentless. Time is suspended, hanging by a silver string. Everyone’s locked into the music: stepping, dancing, ready to keep this precious thing going as long as the bass keeps rolling. Then with a flash the half-light becomes darkness, the huge mirror ball drops its needles and goes black. The Goddess of Light has plunged the club into mystery. And the music stops. Dead.”

At one point in the night, I asked my friend, Jason Bentley, “Do you hear that!?” as I tapped out the percussive rhythm I detected deep in the mix. We were both giddy and wide awake at 3 am. Vasquez would stir in sounds just below the surface to titillate and arouse. His marathon sets were Sunday sermons. The DJ booth was his pulpit. At the risk of sounding cliché, dancing felt instinctual and ritualistic.

I felt a change in the weeks and months after that night. I noticed more new releases that sounded like Junior’s music. My DJing started to emulate his densely layered style.

Looking back, I may have mistaken the end of something as a beginning. The Sound Factory would close a year later. But the confluence of music influencers present and the shared experience of this now legendary night was a high water mark for that era of dance music.

Most well-intentioned dance music histories are incomplete versions of the story. They’re too often missing lived experiences—those first drafts. As the lyrics go, “House is a feeling.” If true, stories can’t be limited to sterile reporting at arm’s length. Experience is vital to music lore.

The term gonzo journalism is credited to the style of Hunter S. Thompson, who injected himself into his writing, blurring the line between traditional journalism and first-person narrative. Following in that spirit, URB’s storied club reviews were helmed by curious souls who came to discover themselves in a blur of underground parties. Their reports mixed immersive first-person confessions with reportage.

Don’t get me wrong: facts, takeaways, and a robust cultural debate are also important. But equally as meaningful is how something made us feel.

I’m more likely to trust the writer who took the pill, jumped the fence, or risked their life rather than the dispassionate bystander. Show me your skin is in the game, and you’ve got my attention. The best stories are the ones we live to tell.

Too well I remember the Northridge earthquake. I thought the Landers quake in '92 was a bad enough introduction to California, being tossed off the couch in my living room; Northridge threw me out of my bed and knocked racks of CDs, my bicycle and pretty much everything standing down to the floor. How I managed to get out of my WeHo studio apartment on the ground floor (under 3 more stories and on top of the garage) without breaking a leg is beyond me. No power, the smell of gas and all I could think of was grabbing my (bag) cell phone, a jacket, and making sure the door would open; then "the car!!!" The elevator wasn't working and I couldn't get to the stairs to the garage. Went outside and, without power, I was able to push the gate to the garage open. Found my car, as did a couple of other residents, and we pushed our cars to the gate where the garage was open to the outside before we started our cars to get them up to the street, because remember - the smell of gas. Sitting outside on the trunk of my car, calling family east of the Rockies to let them know I was okay (the bag phone worked! + kept charged by the car!) watching the blue sparks of transformers blowing in different areas of L.A. county, one of the residents of the building came up to me and asked if he could bum a smoke from me, as he left his inside and didn't want to "chance it." Sure! He said "this is a strange way to have to meet your neighbors." Oh, that neighbor was Warren Zevon. Yes, a strange way to meet the neighbors.

https://youtu.be/0x6mCqcy0XU?si=rs9BXnBpVBfnbbh2