Hip-hop’s relationship with its sexuality has come a long way. Sixteen years ago, there were almost no out gay rappers, much less ones on horseback in rhinestone chaps. Presidential hopeful Barrack Obama had yet to endorse same-sex marriage. Gen Z was only about 11 years old and hadn’t yet scrambled their parents’ brains with talk of sexual fluidity and non-binary. And Jay-Z was years away from walking his mom down the aisle with another woman. But in the mid-2000s, there were signs of change, including Michael K. Williams’ portrayal of onscreen gay gangsta Omar Little in “The Wire,” whose haunting whistling of “The Farmer in the Dell” inspired our title.

The article below, published in June 2007, is a glimpse behind the curtains of an LA club night catering to gay and predominately black hip-hop fans. It was written by our own Brandon Perkins and, at the time, stood relatively alone among the day’s music magazines in its celebration of queer hip-hop culture. And not to give us more credit than we’re due, but validation that we’d at least handled the subject well came in the form of a GLAAD media award nomination. And not to take anything away from our writer, upon reflection on the story’s authorship, I have to ask if we could have been more inclusive.

Like most genres, hip-hop has a long and complicated relationship with queerness. In the early days of this magazine, I called out the contradictions of the early Five Percenter group Poor Righteous Teachers for being conscious while also spitting homophobic lyrics. They were hardly alone in that era. Years later, when Frank Ocean came out lyrically, I’m sure URB would’ve loudly celebrated this milestone had we been still publishing.

Hip-hop and black society are also often wrongfully accused of having an outsized role in America’s stubborn resistance to full LGBTQ equity. In 2008, after Prop 8 in California made same-sex marriage illegal, I wrote a HuffPo piece defending California’s Black voters, who were accused of abandoning gays after the LGBTQ vote helped to elect Obama that same year.

Ultimately, as much as I’d love to see more allyship in hip-hop, it isn’t the sole responsibility of any genre to affirm or support LGBTQ rights. Still, it’s always saddened me that the music that has defined so much of my life struggles to embrace its full humanity. Of course, hip-hop remains only a reflection of a greater society that has yet to.

P.S. Who would have imagined that our “Gay and Gangsta” headline wouldn’t become the most controversial aspect of our cover? We still love you, Maya.

This story originally appeared in URB Issue 147, June 2007

Farmers in the Dell

Behind the closed door of Hollywood’s gay hip-hop club

By Brandon Perkins

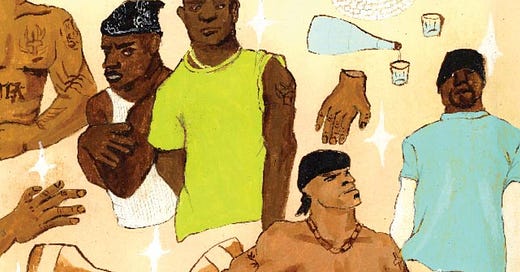

Illustration by Martha Rich

The club is obviously bumping when the sweat-stained stench of sex is thick enough to fog the glasses of even the most cold-faced patrons. It’s not just the nearly naked dancers freaking on a shin-high stage surrounded by lustful stares or the overflowing crunch at the bar, but whatever it is, it’s almost tangible. Urban streetwear brands mark the night’s dress code; glasses are filled with Hynotiq, Hennessy, and Grey Goose, and hyphy tunes from the Bay rhythmically further the frantic pace. “It’s like any other hip-hop booty club,” says the evening’s bartender, “except the girls are also played by guys.”

First Fridayz LA is a moving party throughout the Los Angeles area that has provided its hip-hop crowd of gay black men with a truly unique monthly gathering for five years. Promoted by Ivan Daniel—who also runs the more traditional gay night Club Metro in LA—First Fridayz LA routinely draws between 600 and 700 partiers at various clubs such as Larchmont and Fais Do Do.

“It’s like any other hip-hop booty club, except the girls are also played by guys.”

—Anonymous

“It’s a hot party. It’s a party that’s alternative and caters to all walks of life, but it’s definitely hip-hop,” says Daniel. “Most clubs have kind of a clubby atmosphere. [FFLA] is more of a party, a gathering, social networking, and dancing to hip-hop music. We do it at non-traditional gay clubs so someone who is not in the life or [someone who is] in the life can come and experience this without being intimidated. It’s not a traditional gay club.”

Traditional, it is not, but the crowd at FFLA has one unavoidable similarity to the typical heterosexual hip-hop night: the assertiveness of its patrons. Male-on-male wrestling graces large flat screens, and it’s certainly not what Vince McMahon had in mind. Getting from one end of the club to the other involves circumventing barricades of tightly gripped hands, which create quite the maze, and it’s common to hear strong sexual advances.

“The vibe is very direct, aggressive, macking,” says the bartender (who chose to remain anonymous), “like, ‘What’s up, dog? You ready to get with this dick?’ It’s a little traumatizing even for a non-homophobic fly on the wall.”

As villainous as the black male has been painted in the mainstream media and popular culture, the gay black male has probably had it worse. From the portrayals of prison rape (often for comedic effect) to the ridicule retired NBA player John Amaechi received from Tim Hardaway and others once Amaechi left the closet, gay black men have been painted as walking sex machines like no other demographic. Even the San Francisco bath-houses of the mid-’80s were seen in a better light.

“Within the homophobic Black and Latino communities, gays have to pick and choose where they’re out.”

—Ivan Daniel, Promoter

“We have to worry about the electronic lynching of the black male,” says Daniel, who is very careful of the publicity he gives to FFLA. “I think that there is a significant [down-low] group here, but when you start talking about being in the closet, there are definitely levels. Within the homophobic Black and Latino communities, gays have to pick and choose where they’re out. Some are out to their families. Some are out to their jobs. Some are out to friends. . . There’s a lot of homophobia in those particular communities and in the hip-hop community, especially.”

Although white gay people have had public heroes for more than a decade (Daniel name-checks Will & Grace and Ellen DeGeneres), their black and hip-hop counterpart had no one to turn to until The Wire’s Omar Little. Played by Michael K. Williams on the critically acclaimed (and hip-hop-approved) HBO series, Little is one of the most likable bad dudes in television history. Universally feared and respected, he robs drug dealers, sticks to a strict code, charmingly whistles “The Farmer in the Dell,” and, least notably (due to the superb writing and acting), is gay. Little isn’t a gay character; his character just happens to be gay.

“When you begin to see images of yourself, you begin to start liking yourself more—and that’s in anything,” Daniel says. “When you see similarities in other people, it begins to make you feel a little bit more comfortable because you can say, ‘Oh, there’s someone else like me.’ It creates a comfort zone. We have a lot of [men who look like Little] at First Fridayz.”

Creating a comfortable atmosphere at FFLA— one ripe for the distribution of information—has always been of the utmost importance to Daniel. “The basis of First Fridayz really came about because there was a bunch of brothas and people of a different lifestyle who were unable to meet, connect, and network,” he says. “And because there’s only really one black publication that caters to this genre, information is not readily available. I was a health educator for a couple years, so that was part of the whole concept.”

Much of the information Daniel speaks about revolves around HIV/AIDS awareness, a problem that remains tantamount in the black community—regardless of sexuality. FFLA is careful in its presentation of awareness, making sure that the presence of organizations such as Minority AIDS Project and At the Beach Los Angeles Black Pride are assertive without being overwhelming.

“We are consistently giving prevention messages over the microphone,” Daniel says. “We try to integrate it into the party so it becomes more edible. We will say things like, ‘Wrap it up,’ or ‘No glove, no love.’ We make sure that condoms are on the tables, that there’s prevention messages and programs around.”

That’s certainly something to get hyphy about.

I believe I was really out of touch with what was going on with music and clubbing at that time. I wish I had been more diverse with what I read. Fascinating article. Preface included.