Hip-Hop Love is a Battlefield

Hip-hop's earliest existential fights might be ancient history, but its 50th birthday is a reminder of how far we've come

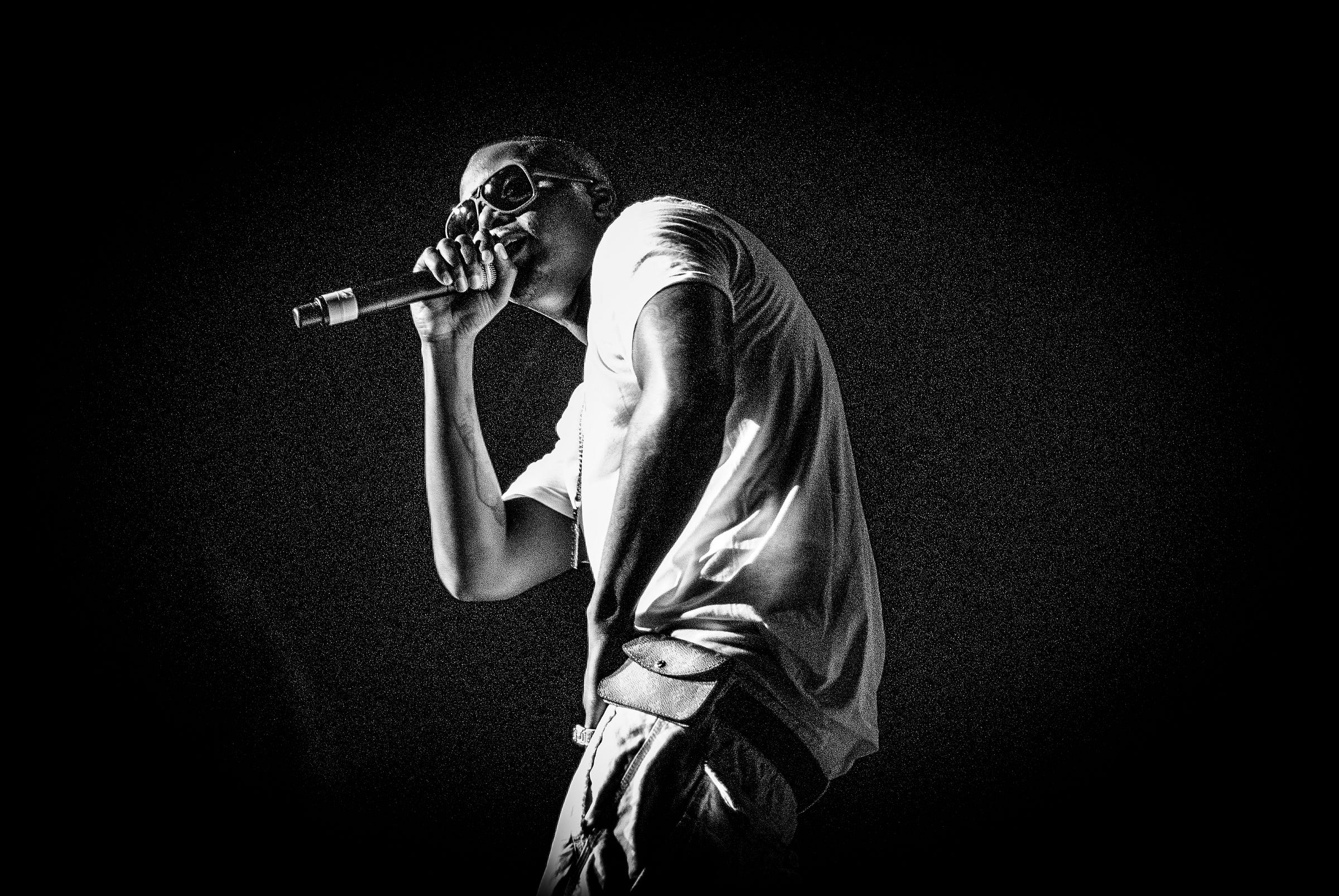

Common’s 1994 call for his beloved hip-hop to return to its true North, “I Used to Love H.E.R.,” came out the same year my frustration with hip-hop was boiling over. Underneath the bouncy and soulful track’s declaration that “hip-hop in its essence is real” (H.E.R.) was a heartfelt battle cry.

Typical for the magazine’s independent and gritty formative days, I unloaded my frustrations in a blistering op-ed called “Ain’t the Devil Happy,” referencing a Jeru the Damaja track with a similarly critical theme. The piece is posted below, and you can be the judge if it rings true years later.

In 2006, for URB’s 15th-anniversary cover featuring Talib Kweli, Questlove, Jean Grae, and El-P, among others, I penned an optimistic follow-up to my ’94 rant. Hip-hop had survived its earlier dalliances with corporate America and became stronger and more resilient. Eventually, I argued, the post-Millineum era of money, power, and respect proved the “war” for hip-hop had been won. Your results may differ, and I can hear the arguments already.

As I write this, I’m sitting in my home studio that opens into a tranquil atrium shaded with Japanese elm trees and bamboo. Inside, it’s a much denser jungle of boxes and shelves, with neat piles of evidence from a culture I’ve lived and celebrated for over three decades. A glass door, allowing in the only source of natural light, is shut behind me so I can focus. It’s quiet, minus the hum of a large hard drive and my middle fingers hunting and pecking away on the keyboard. I type this way, not by touch, because URB’s cofounder Mark Bankins was a major influence in my early years.

Decades ago, Mark and I worked entry-level music industry jobs in a sprawling downtown LA corporate warehouse. Over the previous Summer, we started to plot the launch of a music magazine. Creating it was Mark’s idea, even though its direction was mostly mine. Just out of college, Mark was impressive and knew his way around early Apple Macintosh computers far better than I did. I imitated his hacker-esque and blazing-fast typing style. Many editors would guide my growth as a writer and publisher, including my mom, a news reporter for a time, but Mark was my first editor.

In our December 1990 launch issue, he wrote about the arrest of Charles Freeman, a Black Florida record store owner, charged with obscenity for selling 2 Live Crew’s music. Yes, that was a thing back then. On the back cover of that 24-page oversized newsprint issue was a full-page ad with the headline, FUCK CEN***SHIP, and a promotion for new albums from Ice Cube, Geto Boys, Too Short, and Eazy-E. The asterisks we purposefully placed to make a point about where we stood. Inside was a Jungle Brothers interview I arranged with legendary manager Chris Lighty. Mark stated in the editor’s notes describing why we started URB, “We love hip-hop.”

Thirty years ago, hip-hop was on the ropes and in a war for its survival, not to mention legitimacy.

“When you hear ‘muthafucka’ 87 times in an N.W.A cut,” Mark wrote, “you have to know it’s more defensive than offensive.” He was responding to the oppressive mood of the day when well-connected political activists like Tipper Gore and C. Delores Tucker had it out for this music. It's hard to imagine, but thirty years ago, hip-hop was on the ropes and in a war for its survival, not to mention legitimacy. Store owners that sold hardcore rap music were under threat of jail, Congress kicked off hearings on “offensive” lyrical content, and the “EXPLICIT” stickers only parents of young kids pay attention to today could get your music banned.

Thankfully, hip-hop has grown to where it doesn’t need my or anybody else’s approval. And even when I’m critical, my love for H.E.R. is unconditional. We may go weeks or months estranged or spend hours in nostalgic bliss. Either way, I’m committed. At this milestone, as Common did almost 30 years ago, I’m choosing to reflect on our life together, replaying the highlights in my head. The rest, for better or worse, is just part of the struggle.

Published in issue 39, November 1994.

Ain’t The Devil Happy

The Impending Impotence of Hip-hop

THEY USED TO DO IT OUT IN THE PARK. Not very often these days, however. Today it’s done in corporate towers on Madison Avenue and in Century City high-rises. The essence of hip-hop has slid dangerously away from our control. So far from its initial purpose and significance that it is close to irreparable. The death of hip-hop will be a subtle, quiet lapse into a social and cultural coma. It is a passing that has been prophesied many times before on these pages and others. But still, the forces that continue to drive it over the edge remain unchallenged and are only referred to in cliché attacks from rap artists and journalists. Couple this with a lack of real commitment to saving hip-hop, and all you have is poetic B-boys trumpeting the “true school” while hanging the devils in lyrical effigy. The bottom line is that the so-called “devil” is not the issue here. Sellouts and “new school” bandits aren’t either. The issue is you: The hip-hop brethren, the DJ, the KDAY and WBLS alumni, the worn-out puma motherfucker with an original Critical Beatdown LP in your crate.

The key problem with hip-hop is that it has lost a tremendous amount of control over its destiny— and even its history. It has less to do with race than is purported. Casting stones at the white man—who presses the record that you buy after hearing it on his radio station advertising their products—is bullshit. A tired-ass hypocritical excuse for hip-hop radicalism. Your stones would be better aimed at the artist who signed with the Devil label. As rap continues to sell itself to the “man” in hopes of reaching the masses, it is undercutting the years of cultural and human achievement that have gotten us to this point. The park jams of 1979 were never intended to be a video broadcast from some billion-dollar Viacom satellite. The obscure beats of Kool Herc’s vinyl arsenal were just fine without an accompanying shoe endorsement.

Hip-hop was a reaction to the conditions of the primarily black and Puerto-Rican inner city youth of New York. The inner city is a by-product of greater America’s lack of concern for people of color. For too many years, the system had crushed the dreams of so many kids who were simply born into it that the frustration eventually oozed out in a loud enough form—audible beats and rhymes. How can a corporate America that occupies 80-story buildings—but could never “see” into the ghetto—all of a sudden be home to a musical form that its ignorance was a partial catalyst for?

Unfortunately, the structure of this industry (for many, it stopped being a lifestyle a few years back) is such that a reversal of the mega-growth over the last 5-10 years would be quite painful. Who’s gonna ask today’s big-name acts to sign with small independents and spend the week doing low-key promotional appearances at mom-and-pop retail stores? Instead, appearing at Time Warner’s (perhaps the largest corporate conglomerate in the free world) Vibe magazine party is the daily operation for much-needed publicity. And who’s gonna ask an up-and-coming artist to hold off signing to a major unless they start an autonomous hip-hop department that shareholders do not control? The reversal of fortune will not go over well, seeing that the houses are mortgaged, and the Audi’s are on 5-year leases. In a music form that is steeped in a competition of who is more “true” or “down,” why can’t the criteria include “who is more willing to forgo the fat bank account and do what’s right for the art?” I’m sure nobody wants to be first.

When Ice-T was pulled off the shelves, and KMD’s “offensive” album art was halted, everyone cried “censorship.” Censorship, however a convenient term it has become, is not inherently wrong. As a governmental tool to suppress ideas and expression, it should be fought with zeal at every infraction. As a business decision, as is the case with record labels exercising their right to operate in any way they want, it is entirely justified. This misguided cry for freedom of speech is wasted on an entity that sees clearly its bottom line— business. And as rap music continues to enslave itself to corporations that have historically stifled—or turned a deaf ear to—the voice of urban youth, don’t expect it to change anytime soon.

As is the case with every significant black music form over the past 50 years, hip-hop is chasing its own shadow. It’s the corporate America tail-wagging Snoop Dogg—sort to speak. We are all guilty of the impending demise of this art form. We have all supported the giant power structure that has come to control hip-hop. We have divided ourselves and lost our way in the colorful lights of Hollywood video shoots and Rolling Stone cover stories. There was a time when you had to pay dues. Now, it’s cool if they just pay you royalties.

Hip-hop in the ’70s was a precursor to what could have been an authentic revolution, not only in sound but in society. Instead, it has become a window into our colorful urban world that the curious pay admission to peer into. So what we have is a sideshow for the mainstream. An odd attraction of carnival acts and noises. We aren’t taken as seriously as we take ourselves, and our future role in society is questionable. The soul sonic force that could have been is instead a bouncy Sprite commercial with our rap “revolutionaries” neatly in tow.

THE BRIDGE IS OVER? As painful as it is to admit, this music may have to take another crucial step before it can evade the corporate hustlers that have pulled up a chair at our table. It may have to skillfully recreate itself and abandon the riches and luxury it has come to represent. There are many true elements in this industry and culture that embrace hip-hop in all its glory and grime. Some even have Madison Avenue addresses. These are the labels, magazines, and businesses to gather around. It has to do with artistic, financial, media, and historical control. The artists have the influence to control it, and the audience has the numbers to demand it. It just takes balls. And hip-hop, I think, used to have them.

Edited for length and clarity.

Published in issue 134, March 2006.

Dancing Not Fighting

I had been part of a guerrilla army of ragtag teenagers all through high school, living hip-hop culture in my own way as a graffiti artist and urban renegade. After junior college, I funneled my angst into co-founding URB in December 1990. Besides just having a passion for design and culture, my plan was to take my guerrilla war above ground with newsprint media as my weapon. Aimed at liberating and celebrating underground music culture, URB started as 24 pages of ink-stained soulful aggression. In many ways, 15 years later, the subterranean war that I waged so fiercely has been won.

When a firmly rooted and genuinely talented producer/MC like Kanye West takes home three Grammys (and with several 2006 nominations at press time), are the old battles about “keeping it real” even relevant? What more could we, the faithful militia, have wanted? The evidence of our success — of the music’s success — is all around us. I was in my car yesterday, fully consumed by the dense stutter-fire beats of 3X cover champ Talib Kweli (and Hi-Tek)’s “Time is Now” on his Talib Confidential mix CD. Over the disc’s 53 minutes, I’m hearing everybody from Snoop to Slim Thug to the backpack all-stars Madlib and MF Doom. The CD is a compilation of everything that’s amazing about hip-hop right now: a head rush of urgent street riot lyrics mixed with confident brown-tinted optimism. It’s at once beautifully raw and brazenly accessible at the same time.

The litmus test for the indie artist used to be avoiding all appearances of success and limiting yourself to small dingy shows with brooding guys in hoodies. But the Neptunes, The Roots, Mos Def, and even Jay-Z have changed all of that. By taking creativity and “realness” to new heights, collaborating across musical lines, or giving shine to emerging names, hip-hop is ripe with a new view of what it is and can be. Maybe the ultimate legitimacy is that our music has evolved to the point where the successful rap star and the underground champ can now occupy the same person.

For some readers of this magazine — especially my beloved old-school cats — this might be more a sign that the war was lost, not won. I have to admit that putting down your guns isn’t as easy as picking them up. In 1995 I wrote an editorial called “Ain’t the Devil Happy,” where I dropped a rant about everything from hip-hop-themed Sprite commercials to major label sellouts (for the record, some folks at the majors can still kiss my ass). I was bitter at what seemed to be a surrender by frontline hip-hop soldiers supposedly fighting the good fight for the true school. Instead, they were getting cozy in their new digs as poster children for corporate America’s new theme music while quality beats and breath control languished on hidden mixtapes. I was still wearing my face mask and ready to ignite some desktop-published C4. But looking back, maybe this wasn’t so much the waning of our battle cry as it was the early sounds of victory.

The moans from the trenches also used to lament the death of the D.A.I.S.Y. Age and hip-hop’s “Golden Era,” but—as good as it all was—that’s just nostalgia. The spirit of those eras lives on in a lot of groups invigorating hip-hop today, especially Mr. Kweli. I use the example of hip-hop’s creative success as the best sign of how far things have come in 15 years. Are we at an apex? I don’t know. But if the goal was to make the music our way and to be a voice beyond the ghetto, then hip-hop has definitely arrived. Encrusted jewels may have largely replaced flower-petaled dashikis, but our music has held no higher prominence and relevance in its history.

..."relax a three-card-monte on a sharp shill!!!!!..."