Rhyming Under Rockets: Israelis and Palestinians Find Solace in Hip-Hop

In 2006, during another time of intense upheaval in the region, we wrote about the MCs addressing conflict through lyrics and cyphers

It seems like we’ve been here too many times before. I can only imagine how those living in the region feel. I’ve traveled to Israel and Palestine twice over the years. Each time, I’m struck by two things: the kindness and warmth of the Middle East and the painfully entangled and complex history concentrated on such a small piece of land. In 2006, our writer Jason Newman spoke to several young MCs and others who saw hip-hop as a way to bring light to their stories—both Israeli and Palestinian. At a minimum, it’s a reminder that in the lyrics are the stories that matter

This article was originally published in URB Issue 141, November 2006. Edited for clarity.

Shalom/Salaam/Word Up

In one of the most polarizing regions in the world, the language of hip-hop divides and unites

by Jason Newman

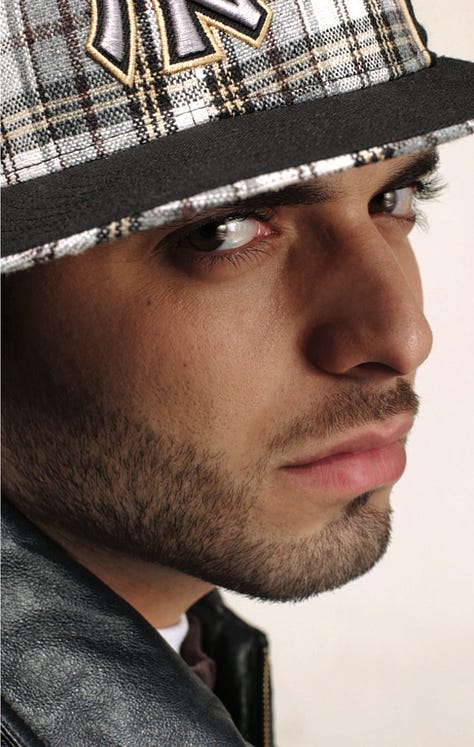

“Sometimes, I used to write my lyrics when the F-16s and the Apaches in the sky were intruding on the people around me. Those things affect me so much and make me feel like there’s something big in me that’s gonna explode my inside. I can describe exactly how I feel through my lyrics.”

The words are from Mohammad F, a 21-year-old rapper born and raised in Gaza. In a part of the world where everyone, regardless of ethnicity or religion, walks the line between everyday life and potential violence, hip-hop has become the new medium for many Israeli and Palestinian youths to tell their side of the story.

The first homegrown hip-hop album came out in 1995 and, while popular, was treated much like American hip-hop back in the day. “At first, Israeli hip-hop was a gimmick. People referred to it as a joke,” says Liron Peeni, founder of “The Biz,” a decade-old hip-hop show on Israeli radio and music columnist for the daily newspaper Yediot Achronot. “It was only in the late ’90s that there were songs that meant something and were not just funny hip-hop.”

Cue 27-year-old Kobi Shimoni, aka Subliminal, who would become the first successful Israeli rapper and—not coincidentally—the most controversial.

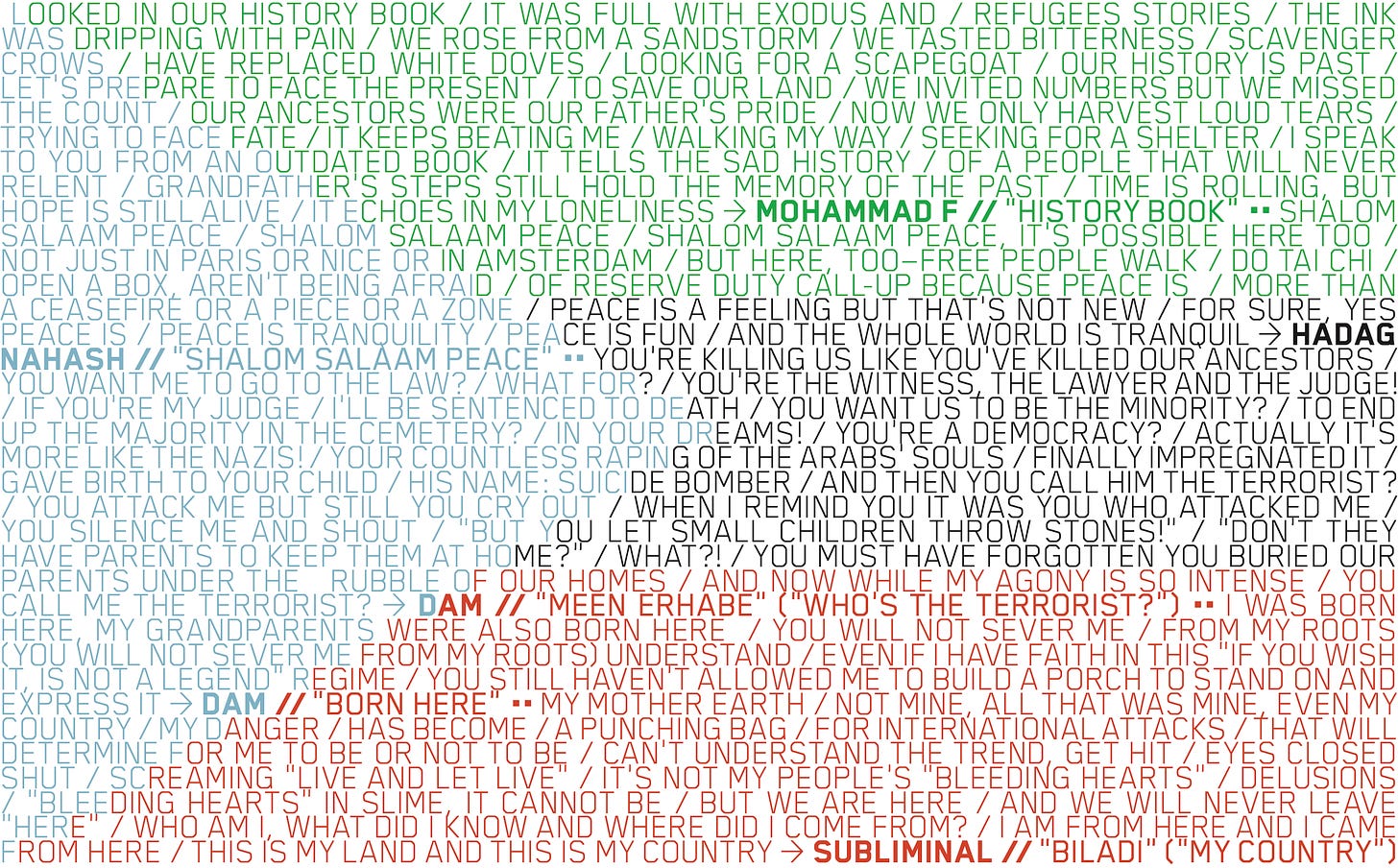

The son of an Iranian father and Tunisian mother, Shimoni, an outspoken nationalist, has released songs titled “Divide and Conquer” and “Biladi” (Arabic for “My Land”) and has been criticized by many Palestinians for what they perceive as extremist views. But while his debut album, Light From Zion, was released in 2000 before the second intifada, many Israeli Jews looked to his fiercely nationalistic lyrics as an outward expression of their feelings.

“When we signed a distribution deal, the first rule was ‘Don’t talk about politics’ because as an Israeli, no matter what you say, half of the people won’t agree with you and won’t buy your album,” he says. “But I think nobody represents Israel as real as me. There is nothing I desire more than peace and nothing I respect more than life, no matter who. For me, it has nothing to do with race. We eat the same hummus and wipe it with the same pita bread. We’re dying, literally dying, to have peace, but there’s nobody to do peace with. They want us dead; that’s it.”

"We’re dying, literally dying, to have peace, but there’s nobody to do peace with. They want us dead; that’s it.”

—Kobi Shimoni, aka Subliminal

Clad in a baggy jersey, baseball hat, and diamond necklace, Subliminal could easily pass for an American MC. With one exception. “The second I got money,” he proudly proclaims, “I bought myself a big-ass diamond necklace with a big Jewish star.” For Subliminal, being Israeli is not just a part of his life; it is his life, and he has been widely credited as re-instilling a sense of Israeli pride among his many followers.

“He had an incredible influence on Israeli youth and brought the Star of David to the forefront of fashion,” says Harry Rubenstein, music writer for the Jerusalem Post. “He also undoubtedly made Israeli pride ‘in’ with the kids, and his Zionistic rhymes spoke to the kids in a language they could easily relate to.” A Star of David necklace was included in the first 20,000 copies of 2002’s Light and the Shadow to show his seriousness.

Among the many future MCs who looked up to Shimoni during his early years was 27-year-old Tamer Nafer. A founding member of DAM, the first and most successful Arabic rap group, Nafer was born in Israel, but, like many Arabs, his roots and heritage lie more with Palestinians than with Israelis. While only 20 minutes away, Nafer’s hometown of Lod, an impoverished city with Jews and Arabs and one of the biggest drug markets in Israel, is a world away from the sophisticated cosmopolitanism of nearby Tel Aviv. Listening to Tupac and similar politically-minded MCs, Nafer says he saw the parallel between his upbringing and American hip-hop. “Hip-hop [in America] started from a minority,” says Nafer. “We are a minority here from people who were living in ghettos. We’re living in ghettos here. From people who don’t have an identity in the USA. We don’t have an identity here.”

Formed in 1998, DAM, consisting of Nafer, his brother Suhell, and Mahmoud Jrere, released “Meen Erhabe.” (“Who’s the Terrorist?”) in 2001. The song, with this chorus: “Who’s the terrorist?/I’m the terrorist?/How am I the terrorist when you’ve taken my land?/Who’s the terrorist?/You’re the terrorist!/You’ve taken everything I own while I’m living in my homeland” immediately became a rallying cry and inspired many Arab and Palestinian youths to grab pens and paper and start spitting their thoughts. If you listen, you can hear love songs and even the occasional party jam, but for DAM and others like him, the anger and pain felt by KRS-One and Public Enemy in ‘80 and ’90s America has been channeled to a similar level here. The group is set to release IHDA’, the first official Palestinian hip-hop album, this fall.

Like DAM, many MCs involved in Palestinian hip-hop use their lyrics to reclaim and remember an identity they feel is quickly slipping away. “Our ancestors were our fathers’ pride,” rhymes Mohammad F in “History Book.” “Now we only harvest loud tears.”

“They’re losing their history, culture, and language,” says Jackie Salloum, director of SlingShot Hip Hop, the first movie to explore the lives of Palestinian rappers. “In schools, they learn Zionist history but don’t learn where they came from. What DAM tries to do within their lyrics is give shout-outs to Palestinian poets, artists, and filmmakers and try to teach the youth.”

In 2003, Salloum borrowed a camera and used various Web resources, such as Arabrap.net, to document the nascent hip-hop scenes in Gaza and the West Bank because of what she saw as a misrepresentation of Palestinians, especially young people.

“When you watch the news in America covering the Middle East, how often do you hear the youth speaking?” She explains, “Hip-hop’s roots are in expressing oneself and talking about what’s happening on the streets. I thought it was just the perfect fit that [Palestinians] took this form of music on as a form of resistance to get their voices out.”

“One of my main goals was to bring the voices out of the MCs,” says Salloum, an American of Palestinian and Syrian descent. “Most people don’t know it’s going on, and they’re talented. I thought it was an amazing way to see another side of Palestine, and music a great way to reach people.”

“When you watch the news in America covering the Middle East, how often do you hear the youth speaking?”

—Jackie Salloum, Director

At one point, Nafer and Shimoni were boys, hanging out and rhyming with each other at shows. But after a June 2001 suicide bombing, Nafer said in an interview that he could relate to the bomber (though not condone his actions). Shimoni became enraged, and the two have been on shaky ground ever since.

“The second [Nafer] got big enough to have his crowd, he started to talk bullshit in Arabic, saying they have an Israeli Zionist enemy and all types of bullshit that Arab kids wanted to hear that have nothing to do with reality,” says Shimoni.

Nafer, for his part, will still rock crowds with Israeli MCs, but Shimoni is not one of them. “In the beginning, before I went political, we were cool,” he says. “When you serve hummus and fix gardens, you are a ‘good’ Arab. But if you want to say, ‘Yeah, I want my rights,’ then it’s ‘Hey man, you’re being one of them.’”

Taking cues from MCs like Nafer, hip-hop in the Gaza Strip has rapidly grown since the first Gaza hip-hop concert in 2004. For rappers born and raised in Gaza, hip-hop is the music of choice for youths to express their side of the story, a side they feel is ignored by the media. “A lot of people don’t know anything about Palestine,” says Mohammad F. “And when they hear about Palestinians, they think we are criminals because of the Zionist media. So, I decided to start rapping to show people how the real Palestinians are. We are not criminals, and we are not bad people.”

Mahmood Shalabi, a 24-year-old rapper living in the Israeli city of Acre, echoes this statement. “We are just saying what we have been hiding inside us for years,” he says. “Using hip-hop, now is the time to tell everything because we can’t hide all the time.”

***

“At the end of the day, the pen is better than any gun. When writing songs, you may hurt people, but you’re not gonna kill them.”

—Liron Peeni

On a recent night at Tel Aviv hip-hop club The G-Spot, while hundreds dance to Subliminal’s beats, a small crowd congregates in another room as the DJ pumps Nas, Jeru the Damaja, and Gang Starr. The yang to Subliminal’s yin, the Israeli hip-hop underground, led by artists like Sagol 59 and Hadag Nahash, thrives and tries to preserve, as one rapper puts it, “the real hip-hop culture.”

“The problem overall is that 25 years of hip-hop foundation does not exist here,” says rapper Shi 360. “They went from nothing to Nelly and skipped the foundation. That’s something that bothers me as a person because the media don’t even consider it a form of music to this day.” Peeni says, “When people try to build a building here, they are starting at the penthouse. They don’t give the time to think about the beginning.”

Like any scene, the commercial vs. underground battle in Israeli hip-hop has existed virtually since the beginning of the genre. Sha’anan Street’s group, Hadag Nahash, had a massive hit with “Shirat Hasticker” (“The Sticker Song”), and he confirms many of his peers’ views about the commercial scene: “You can look at the scene and people try to imitate what they see on MTV. They try to dress and rap like they think a rapper should dress and rap, but it’s going to be removed from our everyday life here.”

“I look at things from an underground artist’s point of view,” says Sagol. “I don’t try to make hits. Sometimes, a song or two will get popular, but I’m not aiming at that. So everything that happens, I take it as a bonus.”

Regardless of aspirations, who share stages with whom gets tricky. Due to movement restrictions, it’s virtually impossible for MCs in Gaza to rock shows in Jerusalem or Tel Aviv. Still, for those living outside the disputed territories, many rappers on both sides regularly perform with each other to crowds of varying diversity. It’s not uncommon, however, for political ideologies to keep some MCs away from others.

No one is naïve enough to think that hip-hop alone can solve such deep divisions between people. But its effect of opening up greater dialogue has been felt since it hit the country. “At the end of the day, the pen is better than any gun,” says Peeni. “When writing songs, you may hurt people, but you’re not gonna kill them. And it’s better to put all your anger into a good rap song that will make people think than grab a gun and kill people. It’s a kind of Middle Eastern therapy for Palestinian and Jewish rappers.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarring_and_feathering