I recently attended a screening of Stop Making Sense, the 1984 Talking Heads concert film by Jonathan Demme. I’d seen the film years ago, but all I could remember was David Byrne’s iconic giant suit and signature jellyfish dance.

But sitting in the theater, watching a 40-year-old performance, I was struck by how enthralled I was as soon as Byrne and bandmates Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, and Jerry Harrison, along with backup singers and multi-instrumentalists, joined him on stage.

I was soon back to the mid-80s era, as captured in the fine celluloid grain of Demme’s cinema cameras. The outfits, the dancing, and the instrumentation all told a story about how culture operated in the art-rock corner of the world. I don’t think it’s hyperbole to say that the audience in the theater, at least a quarter of them dancing in the aisles, was grateful for it being captured four decades ago.

This quirky, self-funded vanity project is now a cult classic and considered one of the greatest concert films ever made. And it was almost lost forever. What a lasting legacy to bestow on the world.

Some films will turn on future generations to sounds and scenes they might have missed by decades, providing a portal to a seminal moment. When post-punk and new wave first made the rounds, I was too busy chasing metal and hip-hop to notice.

Much later, as a more musically mature magazine publisher, I sat and watched Anton Corbijn’s 2007 Control, his black-and-white biopic homage to Joy Division’s Ian Curtis. The dramatized account provided a crucial understanding of the ill-fated lead singer’s life and impact and made me a fan.

Similarly, Michael Winterbottom’s semi-fictionalized 24-Hour Party People about the life and times of the iconic Tony Wilson sent me digging for all the great New Order I’d missed. I’d also come away with a deeper appreciation for Manchester’s early contribution to rave culture.

“When you have to choose between the truth and the legend, print the legend.”

—Tony Wilson

My hunger for seeing our stories “in lights” fuels this archive and me personally. Along with ensuring the material exists to draw from. Selfishly, I want to be part of the storytelling, too. It’s time we all start working together.

Our rich history depends on capturing, preserving, and amplifying this culture—dramatic, non-fiction, animated, whatever. And not just in TikTok posts that will be digital dust in a year but in lasting solid-state narratives.

Yes, there’s a solid Daft Punk documentary. And the Chemical Brothers made one of the best electronic music concert films with 2012’s trippy Don’t Think.

The story of Detroit Techno is long overdue, though this yet-to-be-released documentary looks promising. Regarding the underserved story of electronic dance music, 2018’s What We Started was way better than most attempts. (I can nitpick about its main protagonists being European another time).

Unsurprisingly, several US rave docs and films are in the works. This is great because much of the scene’s heritage remains obscured.

Looking beyond cinema, UK dance music impresario Pete Tong has been touring with a philharmonic orchestra performing dancefloor classics. A 2020 museum exhibit was opened and closed the same year due to the lockdown.

But we need more. Much more. Biopics, podcasts, books, documentaries. As well as musicals, museums, and online archives. No history lasts without consistent investment, steadfast champions, and platforms that survive.

Good stories go untold all the time. The details are forgotten. The characters pass on. The archives vanish. There’s no Stop Making Sense 2023 without the original 1984 footage used to recreate the film.

And memory won’t always serve us. How much of our lives get filed away as scattered and fragmented details? Culture is the same. Usually, when we think back, we see the edited version worth saving. And often it’s wrong.

In my last post, where I talked about my magical night at NYC’s Sound Factory 30 years ago, it was hard to recall all the details. An experience I once recollected as crisp as yesterday was now a bit fuzzy. And I was in the room!

Like so many “life-changing” moments in underground culture, the knowledge is tribal, shared to select followers in blog entries, legendary tales, or a coded language between friends. Protected histories, further isolated by limited media and “no cameras allowed” policies of the past, place them further out of reach.

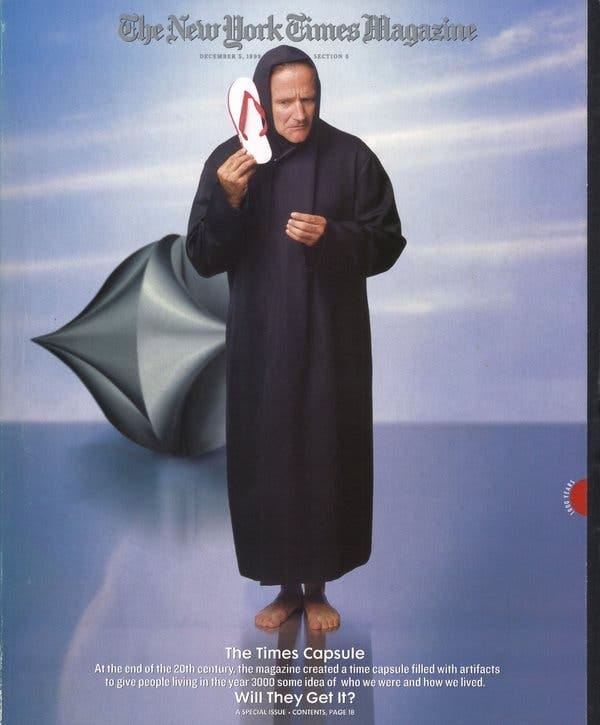

In 1999, I was invited to contribute to a time capsule that The New York Times created, marking the end of the last century. Along with luminaries such as Brian Wilson (of the Beach Boys) and Quincy Jones, a much less-known group of us contributed music artifacts for burial deep underneath Manhattan.

My mixed CD from the same year, Altered States of Drum & Bass (conveniently subtitled “A collection of century-ending breakbeat”), was included as part of a nickel-plated LP squirreled away for future lifeforms, aliens, or whoever stumbled upon the shiny metallic hatch hundreds of years after we’re all gone.

The end of the millennium was a time to reflect and think about the future. The Gray Lady was doing her part to ensure something—in my case, the scene-defining sound of jungle music, hardly a mainstream taste—had its place in future consciousness.

But as David Byrne famously said in the 1980s, “How did I get here?” How does anything from the corners of culture, outside of the popular glare, get included in the historical record besides dumb luck and a good publicist? My drum & bass CD may be the rare piece of breakbeat culture to serve as a sonic hieroglyph 1,000 years from now. It may survive because it truly went back underground.

Most 90s mixtapes won’t physically last another 20 years without the help of places like the Mixtape Museum, Pure Acid (old-school mixtape vendor), or the next time capsule. Digital versions are lost in streaming purgatory, unable—or unworthy—of licensing by most platforms.

There are very excellent sources of ripped tapes—thank god. HD Mixtapes, The Mixtape Archive, and Remastered Rave Cassettes are expansive online collections painstakingly digitized for posterity. Sadly, Simfonik, one of the pioneers in sourcing and posting classic tapes, closed its site in 2020.

Proving the fragility of personal archives, after years of collecting, digitizing, and posting mixes, Simfonik’s disappearance came down to server costs and good old-fashioned perseverance. (In a Facebook post, they’ve promised to have the mixes available in the cloud, so fingers crossed.)

Surviving physical’ 90s-era mixtapes are hoarded, sold, and traded online through Facebook (like I Love Mixtapes) and, I presume, Reddit. If you can’t score it on one of those, that life-changing deep trance mix you remember bumping in the Honda on the way to the desert has probably left the chat.

Full of more DJ Drama (sorry, not sorry) than dance music, at least hip-hop mixtape culture got its deserving documentary treatment in the 2022 film Mixtape. Amplified by hip-hop’s 50th celebrations, there’s a rich story to illustrate on film. Whereas without something more than online links, dance music’s cassette lore may soon be an urban legend for aging ravers to tell their grandkids about.

As a writer, archivist, and documentarian, I’m obsessed with the past, present, and future, which would make my grade school history teachers smile. I’ve spent my career looking into the past, capturing the present, and safeguarding future stories.

I talked with a friend the other night, and we both agreed that some of our historical lethargy is due to a lack of vision. I also think it’s generational. We have been conditioned to be satisfied with constantly feeding ephemeral content into an online beast. In these hyper-accelerated times, legacy seems less important as we quickly cycle through sounds and artists.

Getting my Viral Hits-obsessed 12-year-old to consider anything past next weekend is impossible. And why should she? The content density surrounding modern music fans is immense and seemingly endless. She lives in an always-on and evergreen society.

But the future doesn’t simply take care of itself. Humans must create lasting memories, artifacts must be safeguarded, and moments must be recorded in whatever medium serves them.

Journalists must continue writing, and photographers must capture the images that will tell those stories someday.

Documentary filmmakers must take time to build a case or illuminate a piece of the puzzle. Books need to be written. I need to write mine.

Opinions must be recorded, even if they become relics of the era. Or, in this highly contentious era, risk cancelation.

Of course, AI might step in to save us. Maybe we won’t need humans to explain the significance of Daft Punk’s Coachella performance when real robots can do it better.

But AI can only reflect the components of our human universe and collective memory. So many esoteric underground movements required that you had to be there. Debates around what happened are still trapped in messy Reddit threads, Facebook echo chambers, and explainer videos made by folks who were not there.

If I ask AI about that Sound Factory night in ’94, it will not know because we haven’t told that story yet. This only demands that we bear witness and insist on authentic storytelling, if only as a counterweight to the coming post-reality world we’re barreling into.

It’s great to know exhibits, films, podcasts, and books are underway, many by prominent cultural fixtures and participants. The purge of writers from traditional media might signal even more projects as displaced storytellers find new income streams.

Places like Substack have inspired a return to blogging and a new home for music journalism, adding to the cultural record. There are simply many more tools for recording and amplifying history.

A vast amount of material still exists in untold stories, aging and precarious analog media, or as scribbled footnotes and hazy urban legends when they should be immortalized source material for lasting documentation. Even AI will need to be able to find our stories to tell them someday.

In 50 or even 100 years, what will they know about how the music felt today? And what will be the litmus test for what survives to communicate with a future generation? What will the lasting narratives be? What decades-old story will still be on repeat? What will be long forgotten? What will they find in the time capsule? As with all of history, the answers are up to us.

Great read! 24 Hour Party People is one of my favorite movies about that time period. I'd seen Stop Making Sense 3 or 4 times after it originally came out, I really want to see this again. How did I space on your CD getting into the NYT time capsule? I've added it to the "Coolest things about Ray" list.

There's a documentary on Chicago's Hip-House scene on Xfinity, FYI.

https://corporate.comcast.com/press/releases/300-studios-black-experience-xfinity-docuseries-dna-hip-house

Recently I found a box of cassettes - some mixtapes that I had not listened to in quite a while, of my (mis)adventures through House Music live sets that I did in clubs and fortunately recorded. Many of my tapes were sold out of the DJ booth after I made 10-15 copies to people who would come to the club and ask for them. I wish I had kept more. I've posted 4 of the most listenable tapes on some of the popular DJ sites. One is from LA in 1992 when I landed in WeHo.