This is Dedicated: Goodbye to J Dilla

Reflecting on James Dewitt Yancey, aka J Dilla, and the culture of loss

Originally published in 2006

When the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia died on August 9, 1995, I was surprised at my reaction. It was the first time I remember being sad for his fans. You come to take cultural icons like him for granted. You expect to see them on Behind the Music but also assume they’ll outlive us all (Keith Richards, everybody). So when the Dead’s benevolent tie-dyed priest passed on, it resonated with me purely because I understood that it impacted so many others moved by his music for so long. I didn’t have to own his albums to understand the mammoth void he would leave.

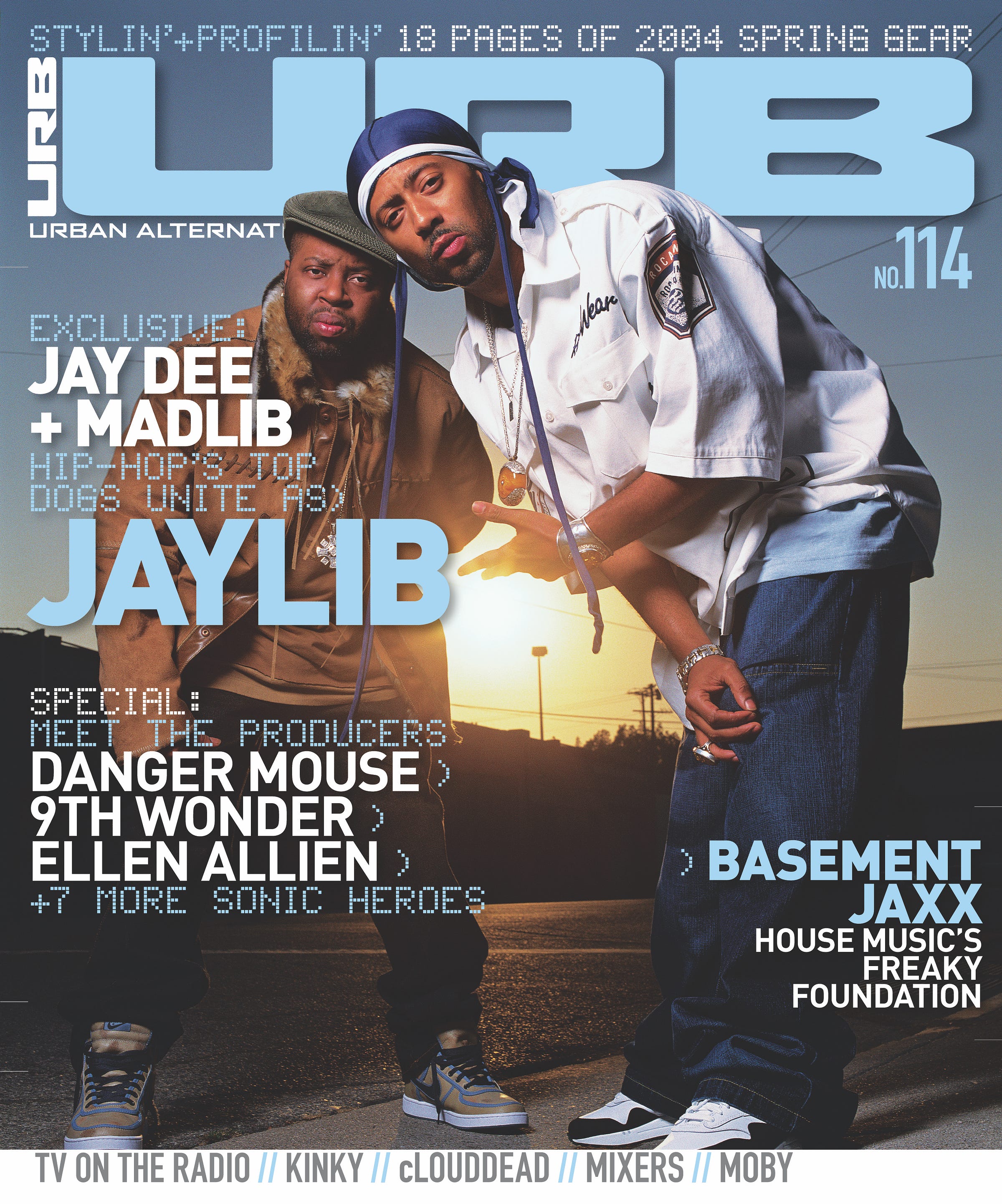

Before he passed away on February 10, at 32, James Yancey had also spent his life making music for us. As Jay Dee (and more recently J Dilla), he will be remembered for his prolific and otherworldly mesh of sampled soul and liquid beats. He had been sick with Lupus (initially shared with URB readers in 2004 as an illness related to fatigue), a chronic disease of the immune system, and left this life quietly while staying at his mother’s house in Los Angeles. Jay Dee had just released the posthumously acclaimed album Donuts a few days prior.

As posts immediately sprouted up after Jay Dee’s passing, it was apparent he had touched many lives. This month’s entire letters section commemorates him. Jay Dee had the privilege and gift of connecting the notoriously snooty hip-hop underground and its star power with his raw but genius productions. And while he never saw Grammy gold or rolled off your moms’ tongue like the omnipresent “Can-yay” West rolls off my mom’s, he was more a hero to the true believers than anybody else I’ve witnessed since Biggie.

Over New Year’s, I made my second post-Katrina visit to New Orleans and witnessed the most devastated areas of the Lower 9th Ward. Row after row of streets was utterly silenced save the lone resident living off propane and batteries. People have described New Orleans as a city with a characteristic sound, and now it‘s inaudible. Very slowly, though, life is edging its way back into the streets and sounds of the city. It’s not a vibrant process and will take years, especially at the unbelievably inept pace. But some of the first stirs of life again are those sounds of New Orleans. Jay Dee has some fans along the Gulf Coast who will add his beats to their rebirth soundtrack.

Death is no topic to tackle in a 600-word editorial. But when it becomes so public and universal—and seemingly with every year I notch off on this life — it feels more a part of the ether. I’ve cried at the pictures broadcast from my city of New Orleans. And I’ve been floored by the passing of several parents of loved ones, friends, and associates in the past year. Each one renders me speechless and later clamoring for the phone to tell my mother I love her.

The longer I live, and the more time that passes where I have healthy people around me, the more I’m sure my “luck” will soon run out. Is that a morbid neurosis, a fact of growing older, or just conditioning? Admittedly, watching nearly every episode of Six Feet Under probably doesn’t help . . . or does it?

When it comes to the passing of a public figure like Jay Dee, we tend to take our private sadness and sanitize it for broader consumption with events, shout-outs, and Myspace tribute photos. I’m not trivializing that; it’s how we collectively deal with a shared loss. Death isn’t something we’re used to privately, much less with acquaintances, so it all feels like a lot is left unsaid. And maybe after 9/11, Katrina, Darfour, and the epochal tragedies in South Asia, we’re too numb.

I know I am.

P.S. The NYT just released this short documentary on J Dilla.